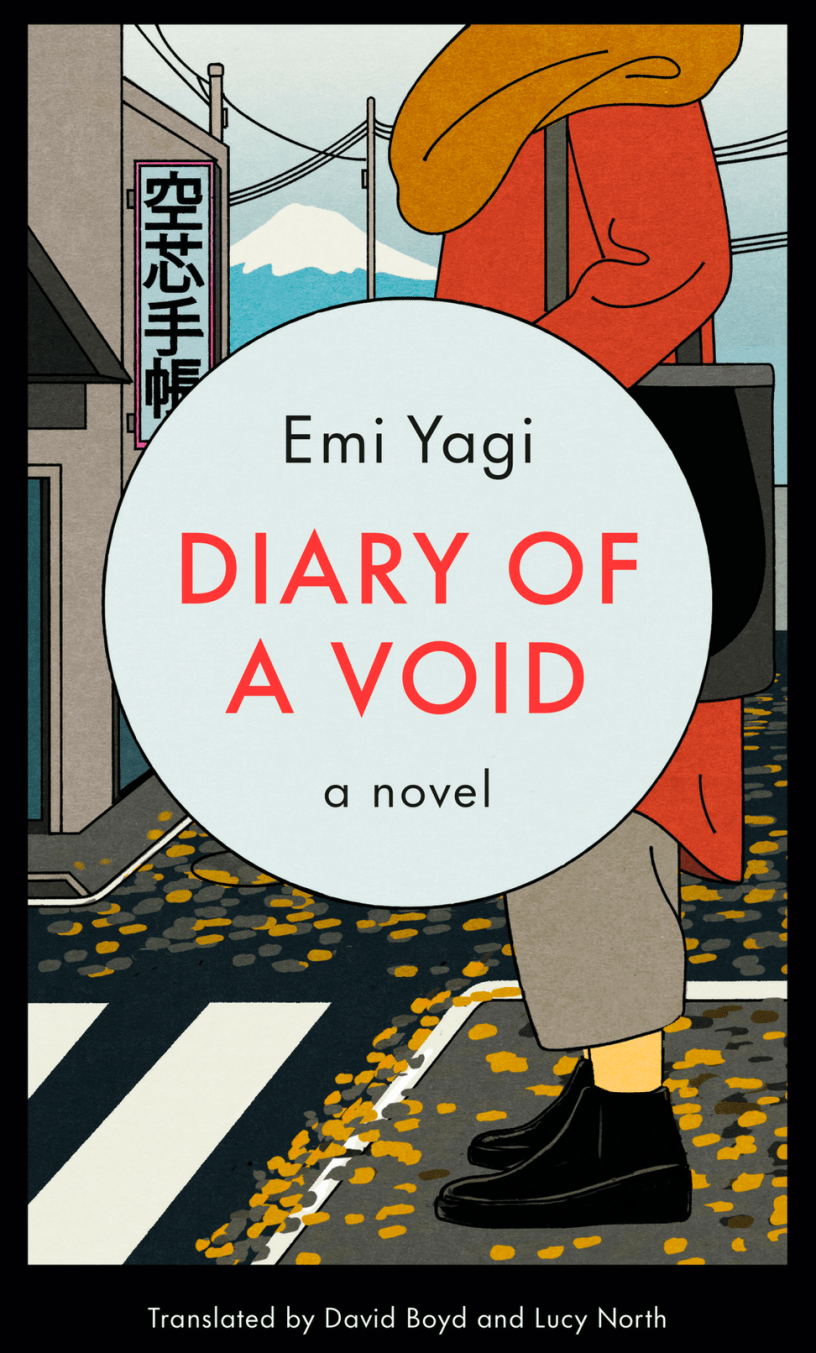

Diary of a Void

By Emi Yagi

Translated by David Boyd and Lucy North

(2020, Trans. 2022)

Viking

Penguin Random House LLC

In the “Translators’ Note,” Boyd and North explain the original title of this short novel alludes to a “Pregnancy Diary” issued by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare to all expectant mothers. The second word refers to the product manufactured by the company the heroine works for: “Empty (cardboard) Cores,” the tubes found at the center of toilet paper rolls, wrapping paper, and wallpaper. They have translated this word as “Void.” Shibata is a college-educated girl stuck in a dead-end job at a male-dominated office. We learn very quickly that her colleagues and superiors are accustomed to having Shibata perform tasks that have somehow been deemed “women’s work.” She is expected to make coffee, distribute mail, supervise birthdays, wash dishes, and clean up after everyone else. She is also the forward-facing company representative, tasked with making uncomfortable phone calls; she can say “no” to buyers, engineers, and manufacturers, but she feels powerless to ask her colleagues to make their own coffee, which is instant, by the way. She decides to change her life and her status by going to her Human Resources officer and explaining that she is pregnant. After everyone in the company recovers from their shock–Shibata never talks about her personal life and is unmarried–the company reduces her responsibilities. Most importantly, she is no longer expected to work till 10 pm or later like the other salarymen. Now leaving regularly at 5 pm, she discovers the trains are far less crowded, food is still fresh and plentiful in the supermarkets, and she has time to pursue personal interests and cook her meals instead of grabbing them on the go. She also buys a pregnancy tracking app. Initially, Shibata finds the app educational, and she also uses it to decide the best way to create a convincing “baby bump.” She receives more and more freedom and deference at work, with the only downside being that she must endure confidential lectures on the likelihood of her having a girl or a boy and unsolicited but nevertheless urgent advice on naming the child. She soon begins eating for two, and when she discovers she is gaining weight she joins an aerobics class for mother-to-be at her local gym. This group becomes her new social network and allows her to hear the perspectives of married women and those having their second or third child. Not surprisingly, as she continues her adventure, Shibata’s grasp on reality becomes fragile. She begins having visions and becomes sure the baby is kicking. She also breaks from her fantasy world to visit her parents, where she finds her mother’s criticism of her lack of a boyfriend and no marriage prospects exquisitely painful. Unlike other unreliable narrators, Shibata’s thought processes are practical and mostly logical, In the end, her simple-to-imitate ruse helps her to restore her health and elevate her status; why don’t more people try it?

What I did wasn’t supposed to be an act of rebellion—more like a little experiment. I was curious. I wanted to see if it even occurred to any of my coworkers, maybe somebody who’d actually been in the meeting, to clean up. “Geez, what a long meeting, I thought it was never gonna end. Oh—the coffee cups. We can’t just leave them like that, right? It’s too much to ask Shibata to do it. I mean, she’s the one who made the coffee for us and brought it over.”

I think I just wanted to know what would happen if nobody was there to keep an eye out, to rush over as soon as the meeting ended and deal with the messes they’d made.

And I still might have obliged had I not been met with the sight of dirty cups, some still with coffee in them, and stuffed with cigarette butts. The odor of old cigarettes left sitting there for hours—it was now four thirty in the afternoon—was too much for me.