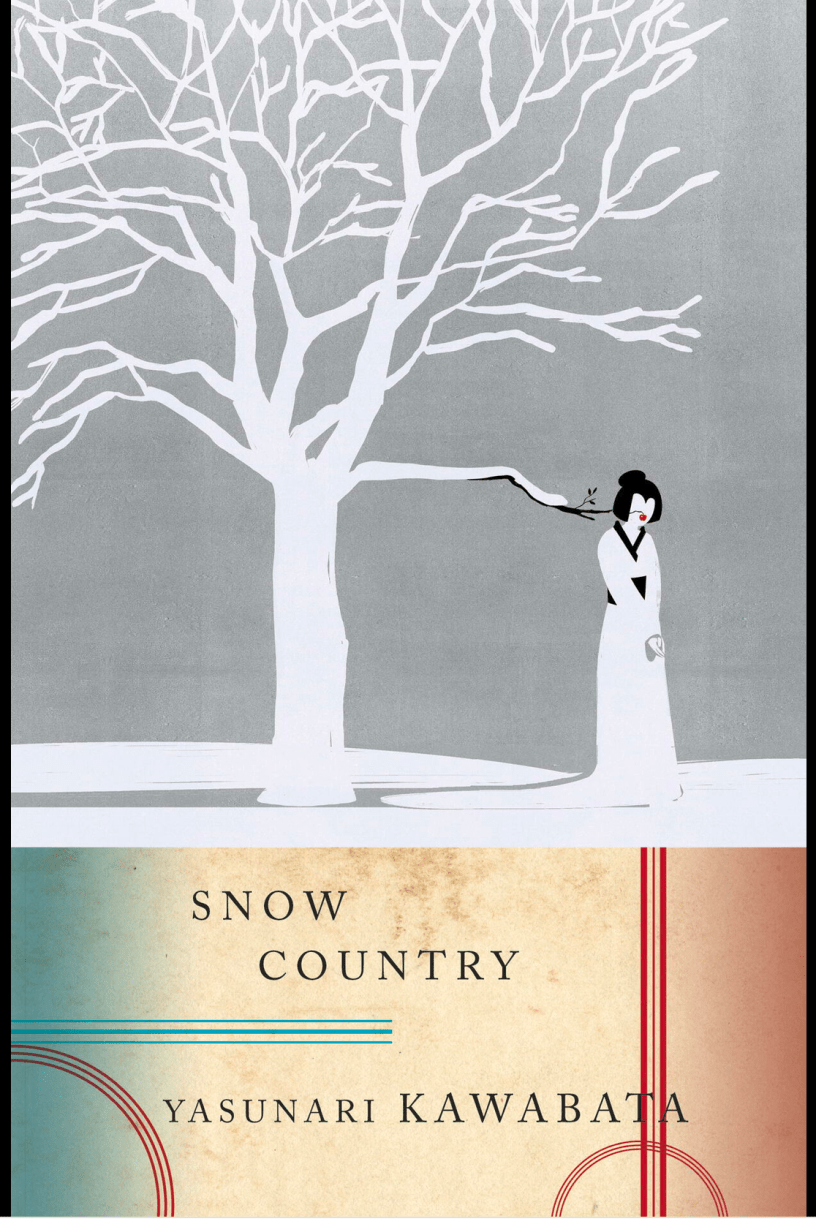

Snow Country

By Kawabata Yasunari

Translated by Edward G Seidensticker

(1935, translated 1956)

Vintage International

(Novel)

Snow Country, considered Yasunari Kawabata’s masterpiece, is set in a small town blessed with a hot spring, good skiing, and a train line connecting it with Tokyo. In the mountains of Niigata Prefecture, snowfall exceeds that of Moscow and Montreal. From the moment the main character enters the region, emerging from a dark rail tunnel into a world of whiteness, Kawabata forces us to see the town through the eyes of a shallow aesthete who regards the area and its people as a spectacle suited to his vision of himself as a man of exquisite cultural refinement. Born into wealth and living off his inheritance, Shimamura considers himself an authority on European ballet and professes to be writing a book on the topic. Married and the father of two children, he has decided to reward himself–as he often does–with a stay at an inn, where, the year before, he had an affair with a young woman named Komako. He renews this relationship but finds Kamako more anxious and talkative during this visit. A skilled samisen player, she reveals that during the last year, her music teacher was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Since then, with the help of another student, Yoko, she has taken on the role of his caregiver. Already unable to support herself, the decision leaves her in further financial peril. Sexually active from the age of fourteen, she takes on a four-year contract as a geisha. Shimamura is largely unmoved by his lover’s fall, but he is unsettled to discover that despite her work, twenty-year-old Kamako has fallen in love with him. She imagines that she can escape her frozen, small-town life if Shimamura will divorce his wife or at the very least, set her up in Tokyo as his mistress. There are further complications, not the least of which is a love triangle. As time passes, Shimamura’s persona of an acolyte of the beautiful is exposed. What he truly seeks in women is a distraction from contemplating his empty life. In the end, he is colder than the mountains of Niigata, a man who finds himself at a loss to understand unselfish and enduring love even when it explodes into action before his very eyes. In addition to skewering Shimamura and his kind, Kawabata introduces his readers to the often overlooked privations of women without families, craftswomen, and women who fly from arranged marriages and follow their hearts.

“The thread of the grass-linen, finer than animal hair, is difficult to work except in the humidity of the snow, it is said, and the dark, cold season is therefore ideal for weaving. The ancients used to add that the way this product of the cold has of feeling cool to the skin in the hottest weather is a play of the principles of light and darkness. This Komako too, who had so fastened herself to him, seemed at center cool, and the remarkable, concentrated warmth was for that fact all the more touching.

But this love would leave behind it nothing so definite as a piece of Chijimi. Though cloth to be worn is among the most short-lived of craftworks, a good piece of Chijimi, if it has been taken care of, can be worn quite unfaded a half-century and more after weaving. As Shimamura thought absently how human intimacies have not even so long a life, the image of Komako as the mother of another man’s children suddenly floated into his mind. He looked around, startled. Possibly he was tired.”