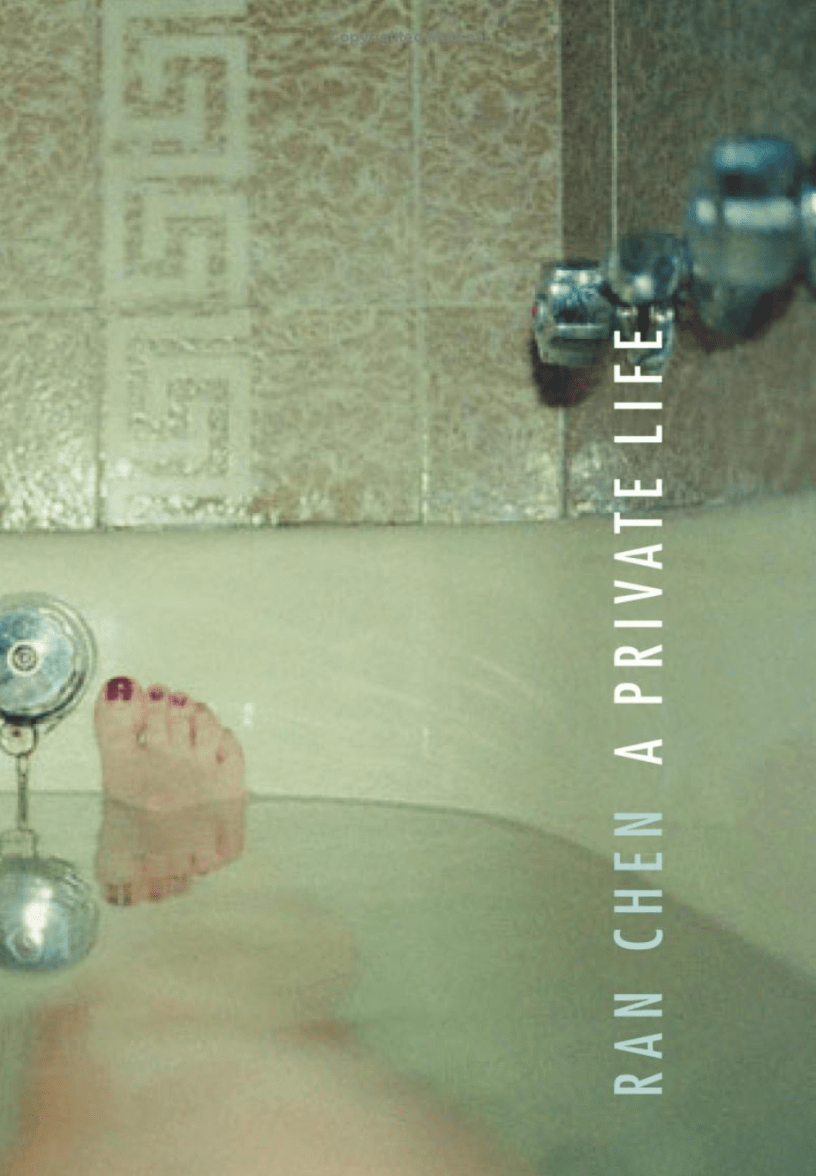

A Private Life

By Chen Ran

Translated by John Howard Gibbon

(1996, translated 2004)

Columbia University Press

(Novel)

Chen Ran is an influential feminist and avant-garde writer; in 1998, she won the first Contemporary China Female Writer’s Award. Feminists praise her writing for its intense focus on life as it is lived by women. In A Private Life, Chen writes from the point of view of a troubled heroine, twenty-six-year-old Beijinger Ni Niuniu, as she reflects on a life of love and loss. Niuniu’s reminiscences unfold without any apparent order; at times the scenes Niuniu describes are dreamlike, and others are almost painfully vivid. The character speaks to us directly, candidly revealing all of her secrets about her childhood, body, bodily functions, desire, sexual experiences, and love. She speaks intimately about the loss of her mother and the gulf that exists between her and her absent father, her relationships with women, and a passionate and self-destructive affair with a successful male writer. She is hospitalized after being struck by a stray bullet and again for mental illness. When the novel ends, Niuniu is still very much herself: uncertain, melancholic, and scarred, but still moving forward. A Private Life proved to be a very popular novel in China, though contemporary critics complained about Chen’s success, accusing her of pandering to the public, exposing too much of her private life, and creating a character who was overly focused on herself as an individual.

This woman is a deep wound,

The sanctuary through which we enter the world.

Our road is the light that shines from her eyes.

The deep wound is our mother,

The mother each of us gives birth to.

I was eleven then, perhaps younger. The late afternoon weather was as unsettled as my mind. The rain would suddenly start pelting down, choosing me as its target. Afterward, I would see that the sleeves covering my skinny arms had angrily twisted themselves into stubborn wrinkles, and that my pant legs, even more obviously angered, as stiff as spindly sticks, kept an uncivil silence.

So I would say to my arms, ‘Misses Don’t, don’t be angry.’ I called my arms ‘the Misses Don’t’ because they most often followed my brain’s bidding.

Then I would say to my legs, ‘Misses Do, let’s go home to Mama, then everything will be okay.’ I called my legs ‘the Misses Do’ because I thought that they most often followed the bidding of my body, paying no attention to my brain.”