The Boy From Clearwater, Volume 1

By Yu Pei-Yun,

Illustrated by Zhu Jian-Xin

Translated by Lin King

(2023)

Chronicle Books

(Graphic Novel)

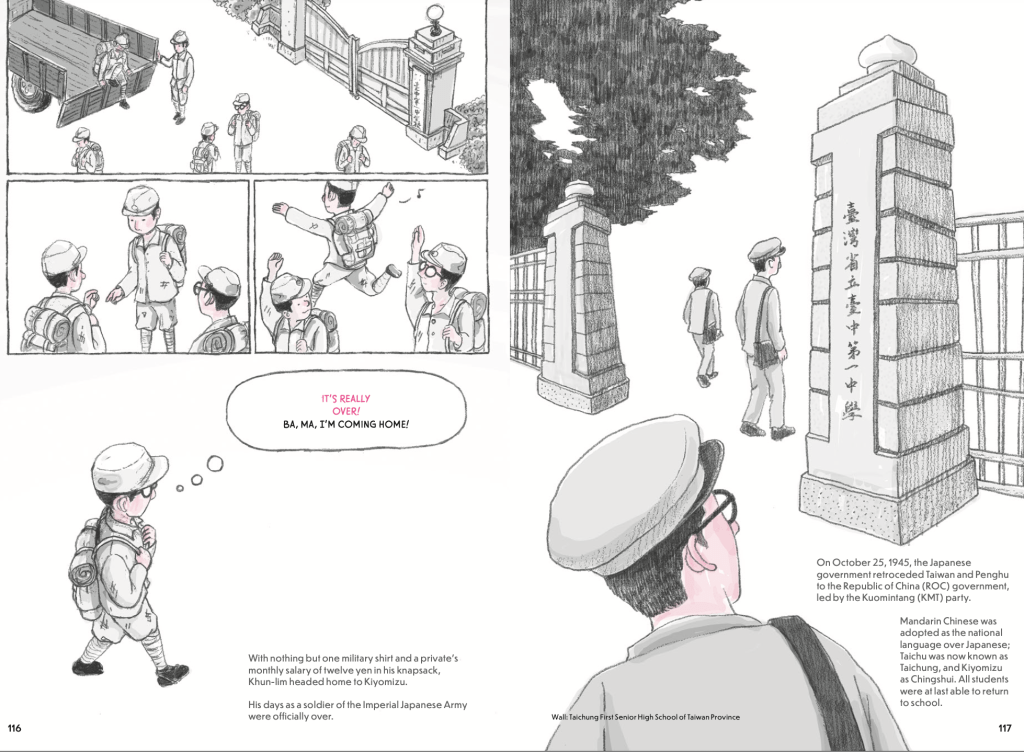

Yu Pei-Yun tells the true story of Tshua Kun-Lim, who was born in 1930 in what is now Chingshui in Taichung City, Taiwan. Kun-Lim is a frail boy with poor eyesight who wants to do his best in school and make his parents proud, a boy who, for the most part, is unaware of the political movements that are radically reshaping the world and the truths he is trying to master. Young Kun-Lim, who dreams of becoming an educator, is completely unaware that a more independent Taiwan ever existed before the arrival of the Japanese colonizers who control the school system. Nor does he know that his father once was part of a resistance movement that fought against the Japanese. These days, Kun-Lim’s father accepts that he and his large family can only survive by embracing Japanization; he even sends Kun-Lim’s older brothers to university in Japan. Kun-Lim, too, becomes a model scholar. He grows up speaking Japanese and attending Japanese schools. He tests into the top school in the region, all along modeling himself on the Japanese nationalist model of academic success, Ninomiya Kinjiro. As the shadow of the Second World War creeps over Taiwan in the 1940s, he becomes aware of food shortages and witnesses the Japanese forcing his father to shut down his department store. In 1945, fourteen-year-old Kun Lim and his entire class are drafted into the Japanese Army and assigned to fortify and defend an airport. They are frightened, but their Japanization is so complete that they see themselves as larger-than-life Japanese patriots. Like true Japanese, when they learn Emperor Hirohito has surrendered, Kun-Lim and his classmates are devastated. They are demobilized, and before the year is out, Taiwan is retroceded to the Republic of China. Now ruled by Chiang Kai Shek’s Kuomintang Party, Taiwan must become Chinese once more. In order to continue their education, Kun-Lim and his classmates must immediately begin learning Pekingese Mandarin. Their old faculty slips away, replaced by Chinese teachers. The students undergo political indoctrination in Sun Yat Sen’s Three Principles: union of the people, government by the people, and welfare of the people. But the abrupt transition leads to crippling inflation, political unrest, protests, and a violent crackdown. In 1947, in order to put down resistance arising in response the the February 28th incident, the government engaged in reprisals that resulted in the deaths of 18,000 civilians. Kun-Lim escapes the initial violence by hiding in the mountains, but his love of learning imperils him. Secret police arrest Kun-Lim, his teacher, and his classmates for reading “communist” writers: Lu Xun, Carlisle, and Hugo. Some are executed, but Kun Lim is fortunate to receive a light sentence: he must serve ten years on Green Island, a prison off the coast of Taiwan. Kun Lim’s story is powerfully told. Despite chronicling the horror of war, the madness of the White Terror, and the inhuman privations suffered on Green Island, author Yu Pei-yun and illustrator Zhu Jian-Xin use a light touch. Violence and destruction take place off-stage. Instead, Yu and Zhu focus on the emotional reactions of Kun Lim and his family. For example, Zhu depicts the B-29 bombing runs over children defending the airport metaphorically, rendering the planes seen through Kun-Lim’s imagination as both bombers and dragonflies. After airstrikes, Zhu focuses on the increasingly dilapidated condition of the airport structures. If lives have been lost, Zhu shows us the grief of the survivors, not graphic depictions of casualties. Even the undercover agent who betrays Kun-Lim to the KMT is merely a shadow. However, as Kun-Lim matures and comes face-to-face with the brutality of the new regime, Zhu shifts to a darker style. He portrays specific torture techniques, including burning a prisoner with a cigarette, beating, stabbing, and electrocution. As shocking as these scenes are, Zhu uses a technique that isolates the site of the pain from the human victim, showing us a close-up of the victim’s forearm, a strategy that avoids sensationalizing the prisoner’s suffering while faithfully documenting their experiences. Zhu’s illustrations are beautiful and affecting, and they are a perfect match for Yu’s presentation of Kun-Lim as a hard-working, honest, and ultimately hopeful human being. This novel is extraordinarily well-suited for use in a secondary school literature or social studies classroom. Yu and Zhu have used Kun-Lim’s story to bring to life the history of modern Taiwan. While Kun Lim’s story is told through multiple panels of characters acting and reacting in medium and close-up shots, the author and illustrator provide precise historical context in documentary-style type over vast cityscapes, historical artifacts like newspapers or legal documents, and drawings based on photos. In addition, at the end of the novel, Yu provides an invaluable three-page-long historical timeline of the events portrayed in The Boy from Clearwater, Volume 1. Most significantly, the author and illustrator have used a wonderfully effective device for revealing the complexity of Taiwan’s story by drawing attention to the many languages of the island. Throughout, the writing in the novel is color-coded to indicate when a character is speaking Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, or Hoklo Taiwanese, which is spoken by the indigenous people of Taiwan. This simple coding is extraordinarily effective at portraying the experience of Kun-Lim during this period – it struck me as vividly and as viscerally as any special effect I have seen in a movie. The graphic novel climaxes with the release of Kun-Lim from Green Island and his return to his family in 1960. I am eager to read the rest of Kun-Lim’s story in Volume 2, and I recommend it enthusiastically to any educator or student who wants to expand their understanding of modern Taiwan and its people.

Many thanks to Chronicle Books for the gifted copy!