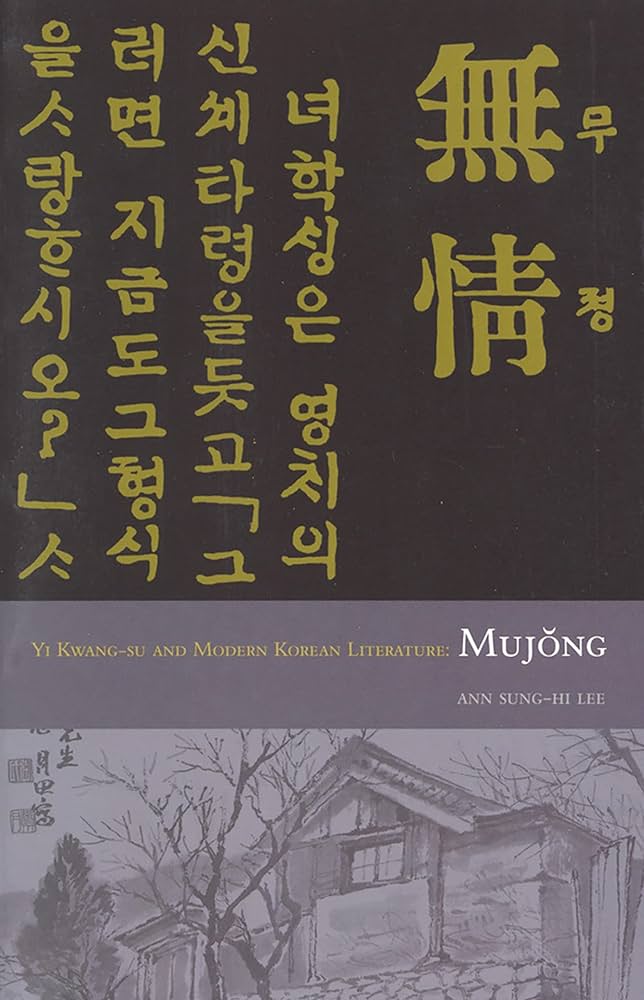

Mujong (The Heartless)

By Yi Kwang-su

Translated by Ann Sung-hi Lee

Cornell East Asia Series

(1917, trans. 2011)

Like Lee Hyoseok, author of Endless Blue Skies, Yi Kwang-su is writing about “the people who wear white,” young Koreans in the early 20th century who are trying to find their way in a world where old social structures are breaking down. Characters in both novels idealize Western industrialization, education, art, and thinking. They view their native land as dangerously behind in all areas and imagine the birth of a modern Korea that will one day be able to stand as equals among the civilizations of the West. This novel’s protagonist is Yi Hyong-sik, a young educator in a Korean middle school who views himself as a brother and father to his students, a mentor who will guide a generation of young men to lead Korea into a brighter future. He rails against the backward practices of Korean education and advocates for radical changes in shaping the mindset of a modern nation. He is moral and chaste to a fault, intolerant of all of his peers save for his friend U-son, whom he badgers relentlessly for his habit of drinking and visiting kisaeng houses. Mujong is also about the relationship between men and women, traditional marriage, and modern love. Though Hyong-sik imagines himself as a progressive, his ideas of love are locked in the chains of tradition. He feels desire but believes love for a woman would debase him. Virtually unable to interact with women in the real world, he ruminates on the affection he shared with the daughter of his grade-school principal, who once jested that the two children should marry. In the years that followed since their idyllic childhood, this child, Pak Jun-Chae, suffered a tragic fall. Her father was wrongly imprisoned when she was thirteen. Jun-Chae, wishing to repay her father’s debts, was deceived into selling herself as a kisaeng girl. She is trained to sing, play music, and entertain men. And although her masters exploit her in every way and she is harassed by beast-like clients, she survives by keeping before her the memory her father’s favorite, Hyong Sik. When she turns nineteen, she finds Yi Hyong-sik and tells him her life story, explaining that she has endured and maintained her chastity in the hopes of reuniting with him. Yi Hyong-sik hesitates. Instead of embracing this heroic woman, he is appalled that the innocent girl of his youth has lived as a kisaeng. He is attracted to her beauty and to the love she represents, but he also obsesses about the purity of her flesh. Is she truly a virgin? How many men have touched her? His cowardice knows no limits, and when she leaves, Jun Chae knows that her dream love has judged her as unworthy. At precisely this moment, a well-to-do member of the jangban class hires Hyong-sik to teach his teenage daughter English; by the end of the month, the father declares that he wants Hyong-sik to become engaged to his daughter and travel to the United States to enroll in college. Again, an unmerited bounty lands at Hyong-sik’s feet, and again, he finds himself unable to make a decision or even muster the shadow of an emotion. He is, at these moments, heartless. Yi Kwang-su declares that the marriage culture of Korea is heartless, too, but he believes that the youth can free themselves of these bonds. Other characters experience powerful awakenings. Women stand out as they are the first to turn their views beyond their own disappointments and sorrows and embrace the people and community around them. For Yi Kwang-su, the lost souls who find themselves at the beginning of a new age can only be whole by being inoculated with the suffering that is life. As he observes so many times, it is suffering that makes them–at last–human beings. And in that moment, they also become true Koreans, capable of healing, inspiring, and leading a nation.

“Son-hyong was still an innocent child who had just fallen from the sky the day before. Today she had tasted for the first time what it was like to be a human being. She had tasted the bittersweet taste of life for the first time, in love’s burning flames, and jealousy’s surging waves. There is an old saying that ‘even skeletons get smallpox once.’ In a similar way, this baptism of life is what everyone suffers. Though it might seem as though there could be no greater happiness than to get by without it, one would feel better off not having been born a human being than not receiving this baptism. Sweet or bitter, it was a destiny that could not be avoided.”