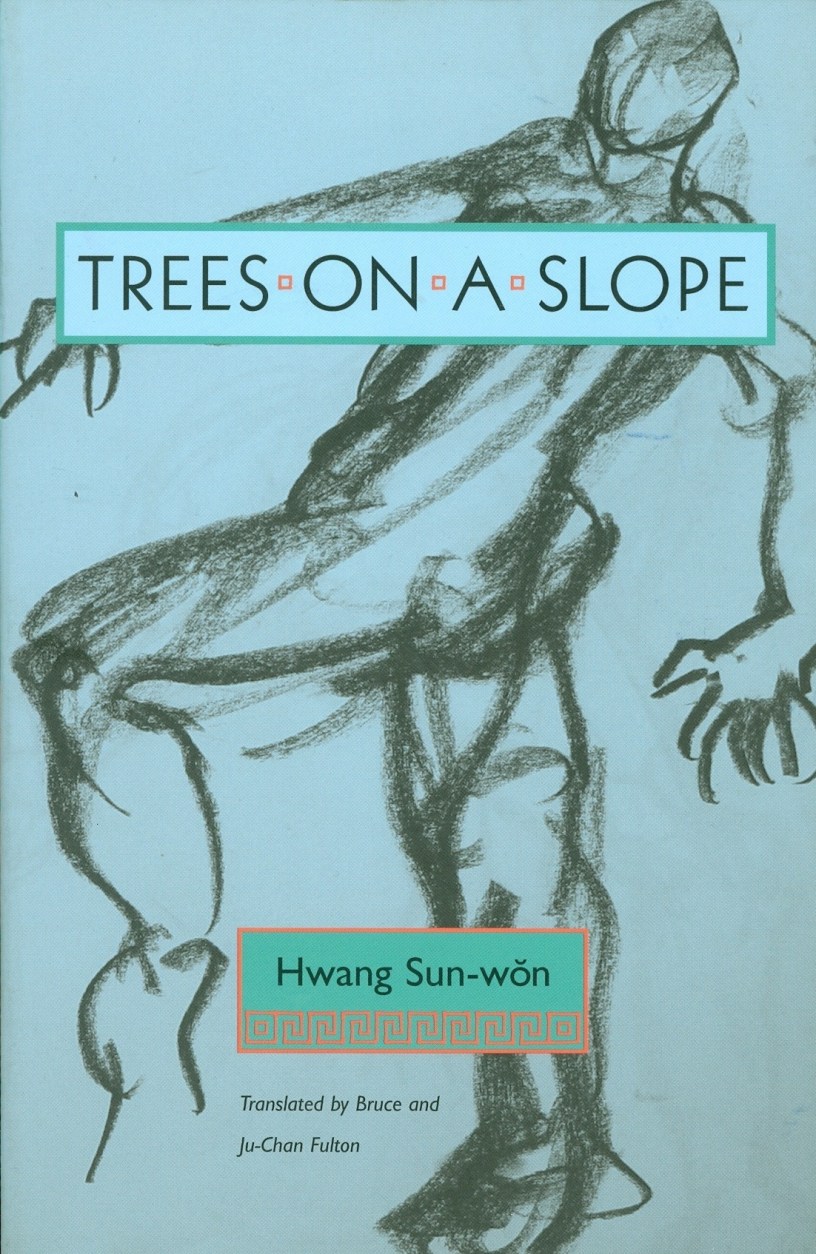

Trees on a Slope

By Hwang Sun-won

Translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton

(1960, translated 2005)

University of Hawai’i Press

Trees on a Slope stands apart as one of the rare war novels to emerge from Korea in the first half of the 20th century. In a helpful afterward by Bruce Fulton, the translator points out that Korean writers, academics, and social critics have been struck by the small number of authors who have directly addressed the violence of the war from the standpoint of the front-line soldier, speculating that their reticence to revisit this still unresolved conflict stems from the internecine nature of the combat. Hwang, who is not a soldier, focuses on the experience of three men who are patrolling the mountains near the 38th parallel at the end of the war. On paper, the line is static and combat has ceased, but in the mountains, troops on both sides are engaged in reconnaissance activities, probing actions, nighttime assaults to secure territory, and even exchanges of artillery fire. The three friends are the squad leader, Hyon-tae, his right-hand man Yun-gu, and the naive and idealistic Tong-ho. To some extent, this is a cast of characters we have seen in countless war novels or movies, but Hwang veers from the tropes of the genre very quickly. Although he does describe the anxiety of being on patrol, the panic of repeated strafing, hand-to-hand combat in the dark, Hwang focuses on the men’s involvement in personal, intimate violence. The soldiers fight for their lives in the heat of battle, but well after the smoke clears and the fog of war settles, they plan and commit murder against innocent and defenseless Koreans, and in many cases, they assault women. After encountering a woman hiding in an abandoned village, one of the team returns to kill her and the child so that she does not reveal their location to the communists. Initially, Hwang presents this event at a distance, as the logical supposition of a soldier who watches his leader double back on a darkened trail. The young soldier sees the assassination as a necessary evil; to some extent, he is even grateful that his leader does not involve him and his buddy in the murder. But Hwang also presents the violence from other points of view so that what was initially hinted at becomes explicitly clear: we learn for certain that the leader sexually assaulted the woman before killing her, and we discover how he executed the infant. Engaging with the enemy, their targets are anonymous; usually, we do not even see their faces. But the more intimate and cruel violence is visited on civilians with whom they share a long history. Hwang focuses on soldiers committing murders or sexual assault on Korean women who have already been victimized by the war. When we meet them, they are either owners of shack-like drinking spots where they sell themselves, their daughters, or other desperate, starving, and ill women. Some have lost husbands, and others have seen their whole families wiped out. They know their lives are worth nothing, and the soldiers know this as well. At times the soldiers confide in these women, at others they exorcize their own demons by abusing or even executing them. In the second half of the novel, Hwang follows the surviving soldiers into post-war Seoul. Hyon-tae’s parents set him up in a cushy office job, but he walked away one day and never returned. His parents continue to fret over him; they have secured a visa for him and they are arranging to send him to begin a new life in America. Yun-Gu has taken loans from Hyon-tae to raise chickens. Plodding, methodical, and intensely loyal, he devotes himself to becoming a responsible chicken farmer and budding entrepreneur. Tong-ho, “the poet,” is long dead, having committed suicide. His fiancee tracks down her beloved’s war buddies, desperate to know why he hid his pain from her and why he committed suicide. Another veteran, a former boxer, joins Hyon-Tae as his new drinking buddy. Throughout, Hwang Sun-won focuses on a generation of men traumatized by an endless civil war and the cycles of violence it sets in motion. As painful as it is, it should be essential reading for those interested in the raw hatred and cruelty these men unleash against their own countrywomen.

“Damn, you should have seen the fuss my girl made over these scars. ‘Just look at that skin, how red it is and smoother than the other–it’s so pretty I could die’…so told her, ‘If you really think it’s swell, why don’t I make you a scar of your own?’ Know what she said? ‘I already have them, more than I can count.’ Good God! ‘And they’ll never heal, as long as I live.’ Now get this. ’If two of us with scars can have a nice life together, I’d never ask for anything more.’ Give me a break! Who’d want to live with a wretched woman who doesn’t shut up? I wasn’t in too good a mood after that.’”