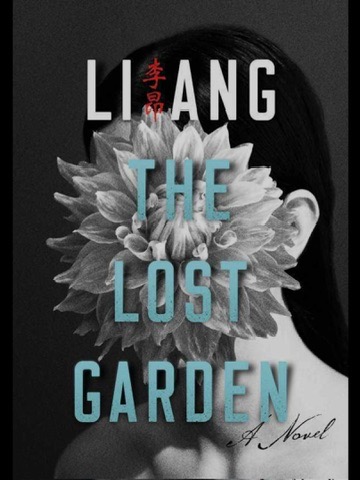

The Lost Garden

By Li Ang

Translated by Sylvia Li Chun Lin

And Howard Goldblatt

1990, Translated 2016

Columbia Iniversity Press

The Lost Garden is a novel about Taiwan, the legacy of the White Terror, and Japanese Colonialism. It is also a slow-burning and perhaps unsatisfying feminist novel, but not so spectacularly defiant and violent as Li Ang’s heroine in The Butcher’s Wife. It is both a cerebral text and “of the body” as well. Li Ang tells the story through two alternating narrators. One witnesses the unfolding of a family history from a distance, the other is the “I” voice of Zhu Yinghong, who grows up in her father’s home, a complex of temples, pavilions, and outbuildings set in a large ornamental garden in Taipei which somehow managed to escape the excavator of modernity. Her father named her Yinghong after one of the pavilions; in Chinese, her name is “shadowy red.” Old Zhu has a long Chinese bloodline and his status is high, but he is a uniquely Taiwanese character, a survivor of great political violence who has gone to ground in the heart of the city. Zhu counts himself as a Taiwanese patriot yet speaks a very proper Japanese with his family. Why? Living under the Japanese occupation of Taiwan, he was educated in Japanese schools. He even arranged to send his sons to school in Japan as well; now they live and work in the United States. But he has kept Yinghong at his side. She is his favorite. In Japanese, he calls her Ayako. When just a child, she remembers soldiers coming to arrest her father in the middle of the night. For many months, he was simply not at home, and when he returned, he was sick for a long time. Even after he was well enough to walk about, he remained in the precincts of the garden. During that time, and for many years after, Ayako/Yinghong and her family remained under government surveillance. It was also during this period that her mother and father switched to using Japanese in the home–even around their faithful servants, Mudan and Luohan. The father, whom the heroine calls Otosan, is a fascinating character in himself. Although he lives a life of concealment and retreat, he alone of all his family argues that their clan must acknowledge their ancestral relationship to a known pirate and admit that their power and influence stem from the wealth accumulated by a privateer. He is the first to bring electric light into the maze-like garden. But as much as The Lost Garden is the story of the male old guard, it is a woman’s tale of negotiating a life in a modern, dynamic Taiwan. Yinghong fashions herself into a highly successful aid in the dizzying world of high-stakes real estate development in Taiwan. Efficient, professional, and attractive, she accompanies the wheelers and dealers to meetings and the required dinners and drinking parties that follow. At a certain point, she realizes that the other women at these parties are prostitutes and that the cards they distribute to the inebriated businessmen are to solicit after-party trade. It is at one of these dinner events that she meets Lin Xigeng, an up-and-coming broker who may have ties to organized crime. Yinghong is attracted to Lin, and here Li Ang transports us into another world of power, conquest, surrender, and reversal. The principles do not slip into other languages to hide their actions and motivations, but Yinghong and Lin engage in a fierce power struggle where each goes to extraordinary lengths to assert dominance over the other. Lin Xigeng and Zhu Yinghong are certainly beautiful creatures. But Lin is forever more distracted by big numbers than love or even desire, and though Yinghong is a sensualist of the first degree who pursues her desires to the utmost, she requires possession of this man far more than she will ever love him. Li Ang portrays them vividly in sexual encounters that are at times titillating, often disturbing, and always transactional. Is Yinghong her father’s daughter, one who will shine a light on the truth, no matter how uncomfortable it is? Or will she keep herself like the garden she has inherited? Whose garden is it, after all? Who constructed a traditional Chinese garden and planted mainland trees and shrubs in Taiwan? Old Zhu had sense enough to destroy old plantings and replace them with native species, but will the garden ever be truly Taiwanese? And will it survive Taiwan’s mad rush to pave over the past?

“When Father wrote this letter, he must have seen flowers from the transplanted star fruit trees flowing down the waterways and reaching into every corner. The tiny teardrops of flowers traveled past pavilions and terraces, through the many ages of the human world and the vicissitudes of life in Lotus Garden.

In addition to planting star fruit trees, Father also cut down the original beech trees on the hill behind Authenticity Study and replaced them with flame trees.

‘The ancients planted beech by their study because it portended good luck at the scholars’ examination. Such feudal beliefs are not only outmoded but should be completely eliminated.’

He turned solemn as he spoke:

‘If one day democracy can be found in Taiwan, the Taiwanese will have a good life, even if it is the Western or Japanese type, even if it’s just a semblance of democracy, so long as no one holds the idea of a mandate from heaven.’”