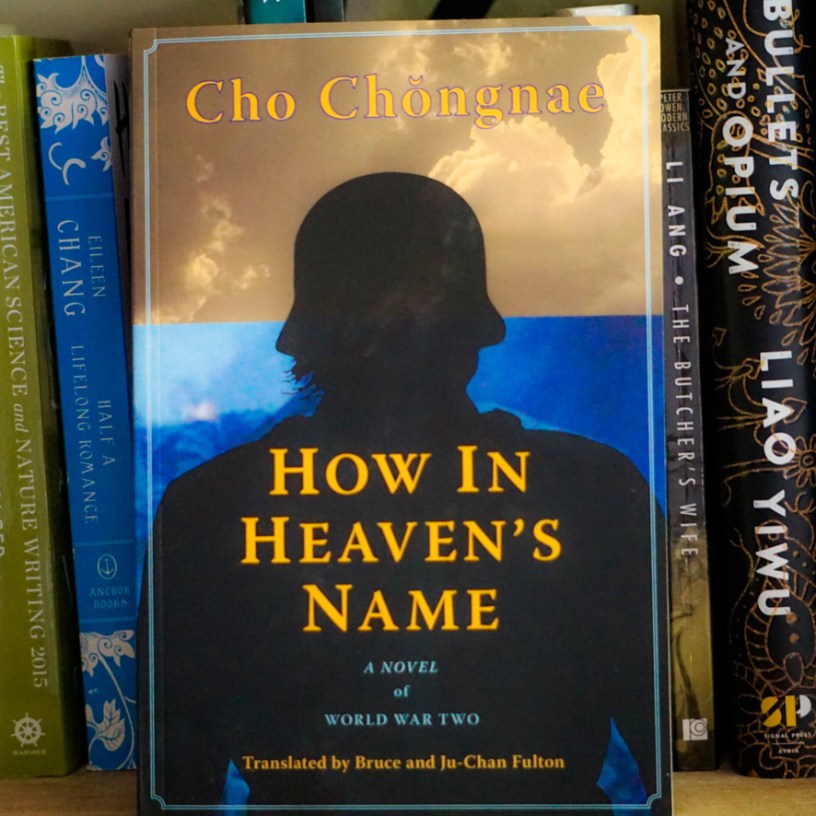

By Cho Chong-nae (Jo Jeong-rae)

Translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton

(2007, trans. 2012)

Merwin Asia

Cho Chong-nae (Jo Jeong-rae) is one of the most popular writers in South Korea. A writing powerhouse, Cho created a highly successful multivolume trilogy of historical fiction focused on the history of 20th-century Korea. The trilogy includes Taebak Mountain Range, Arirang, and Han River and was completed in 2002. Cho wrote How in Heaven’s Name in 2007; unlike his previous work, this novella can be completed in two sittings. Cho’s inspiration is a famous photograph of soldiers captured by Allied forces on D-Day. Among the many exhausted and frightened POWs, the photographer focused on a group of Asian men who later turned out to be citizens of Korea. Cho introduces us to a new window into some of the lesser-known paths of the Korean diaspora. Kilman Shin is a nineteen-year-old Korean. He and his family are starving. Their best chance of success depends on the eldest son finding clerical work under the Japanese. Their wish seems to be about to come true: Japanese colonial government offers to train young Koreans to become clerks. The Japanese require applicants to join the Japanese army, promising the new recruits that they will study and train at camps near their hometowns. It is not long before Kilman Shin realizes that he and his friends have been duped. They are immediately dispatched to the frontlines of the war in Manchuria to fight for the Emperor against Russian and Mongolian troops. When his position is overrun by Russian tanks, he surrenders to Mongolian troops, hoping that they will be more merciful than the Russians. When the Russians learn of his capture, they take possession of him and several other Koreans, who explain that they were forced to fight for the Japanese and ask to be repatriated to their homeland. The Russians explain that the men have two options: in exchange for Russian prisoners, return to the Japanese –which would result in their immediate execution–or join the Red Army. Shin and his fellow prisoners agree to pledge allegiance to Stalin but pull up short when they realize that they are required to become Russian citizens, which requires Shin Kilman to become Mikhail Shin. After several months in a crude prisoner-of-war camp, the Koreans travel east across Russia, where they encounter large numbers of Koreans who fled from the Japanese colonial armies and either threw in their lot with the Russians or were conscripted into their army. Eventually, they are stationed outside of Moscow, where those soldiers who are not killed by the cold or the siege are captured by German soldiers. Shin and others are put on trains and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany, not too distant from a POW camp for Allied soldiers. Shin almost dies of starvation here. The men are fed only water and bread made mostly from filler. They discover that the American and European prisoners are much healthier, not only because the Germans allow them to receive packages from home, but also because Hitler saw these men as similar in racial status to the Germans while regarding Asians as the products of a weaker moral and physical stock. Shin would have died in this camp, but when the Germans realized that the tide was turning and they would face an invasion from England, Shin and the other survivors were drafted into the Wehrmacht and sent to the coast of France to install defensive steel barriers along the beaches. Cho Chong-nae’s plot speeds along as he portrays Korean citizens and Korea as a people and country so powerless and lacking agency that the major power players of the East and West universally regard them as disposable slave labor and cannon fodder.

“Each man in turn received a sheet of paper listing his name in hangul, his Russian name in the zigzag Cyrillic script, and finally a hangul-ized version of the Russian name.

‘Downright strange, one of the men muttered after they had returned to their barracks and were perched on their bunks. ‘It’s not like we’re living the rest of our lives in the USSR, it’s just temporary service–is it really necessary?’

‘It feels kind of stupid–changing your name makes about as much sense as changing your parents.’

‘Yeah, it’s odd for sure. Something about it doesn’t right with me.’

‘I think it’s because they left the family name as is and just changed the first name. Looks funny, doesn’t it? Like a gentleman in an old-fashioned horse-hair hat riding on one of those new-fangled bicycles. Maybe they figured it’s asking too much to change the whole name.”