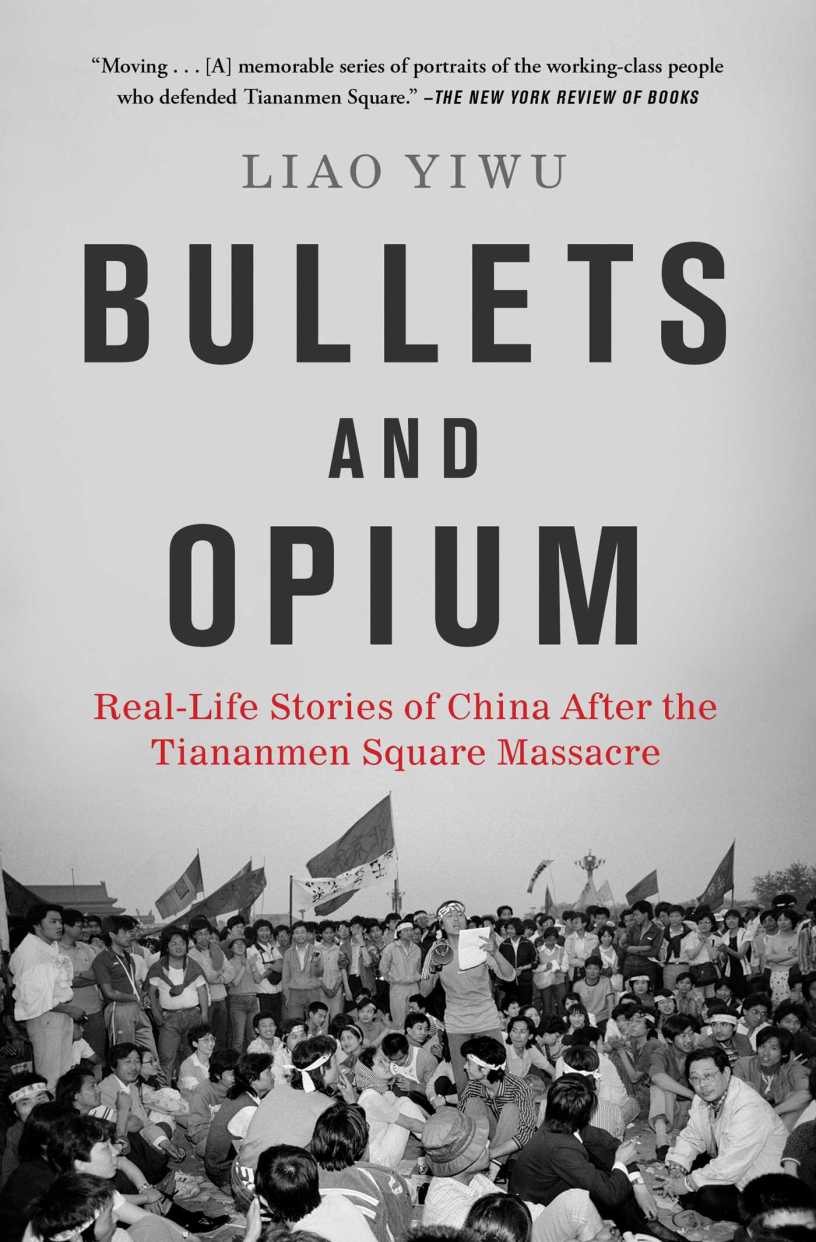

Bullets and Opium (2019)

By Liao Yiwu (m.)

Translated by David and Jessie Cowhig and Ross Perlin

(Non-Fiction, Oral History)

Mr. Liao’s Bullets and Opium is an oral history, a collection of whispered interviews he conducted with average citizens who participated in the Tiananmen Square protests, those who were arrested, imprisoned, and who served between seven and twenty years for their actions. Liao was himself imprisoned for four years for publishing a poem of protest about the Tiananmen massacre (see For a Song and a Hundred Songs). Pointedly, Liao avoids the student leaders of the protests, many of whom were able to use their connections and wealth to flee the country, and instead focuses on the lower-class workers who dropped everything to support the student revolution. He visits with men who painted protest banners and chanted political slogans, those who may or may not have set fire to military trucks, and those who threw paint-filled eggs at the iconic portrait of Mao in Tiananmen Square. His voice is minor in these interviews, prompting, redirecting, and laughing grimly with the interviewees as they recognize their common experiences. Some authors have compared this work and Liao’s The Corpse Walker to the oral histories of Studs Terkel. Liao claims that the bullets of the title refer to the violence the state turns against its citizens in order to maintain its lawless rule. Liao maintains that the state’s reckless embrace of a capitalist economy has created a culture of “Love of money before love of nation,” where the newly rich are willing to tolerate abuses of power as long as the flow of cash continues. Thus, money is the new opium, poisoning the morals of Chinese society. All of the interviewees are men, and virtually all of them report that their time in prison and their frequent torture sessions have left deep emotional scars that have impacted their ability to have sex and be in relationships. Many report divorces; if they speak of new relationships, they speak of it in the context of a miracle. Most are unable to hold down jobs; a few make a dollar in illicit trade. Almost all are dependent on their families, and they live in fear of periodic check-ins from the secret police.

“Soon after, the secret police came and put me under house arrest after I interviewed two Falun Gong practitioners…This time what happened was that two shabbily dressed, very worried-looking women knocked on my door. I thought they were beggars and I let them in. Out of habit I got out my notebook and recorded the horrible treatment they had suffered at a mental institution.

A week later I heard heavy pounding on my door. Fortunately, the door was solid and couldn’t be opened by punching and kicking. In my desperation, I grabbed my bank card and ID card from the drawer, squeezed myself out the kitchen window…”