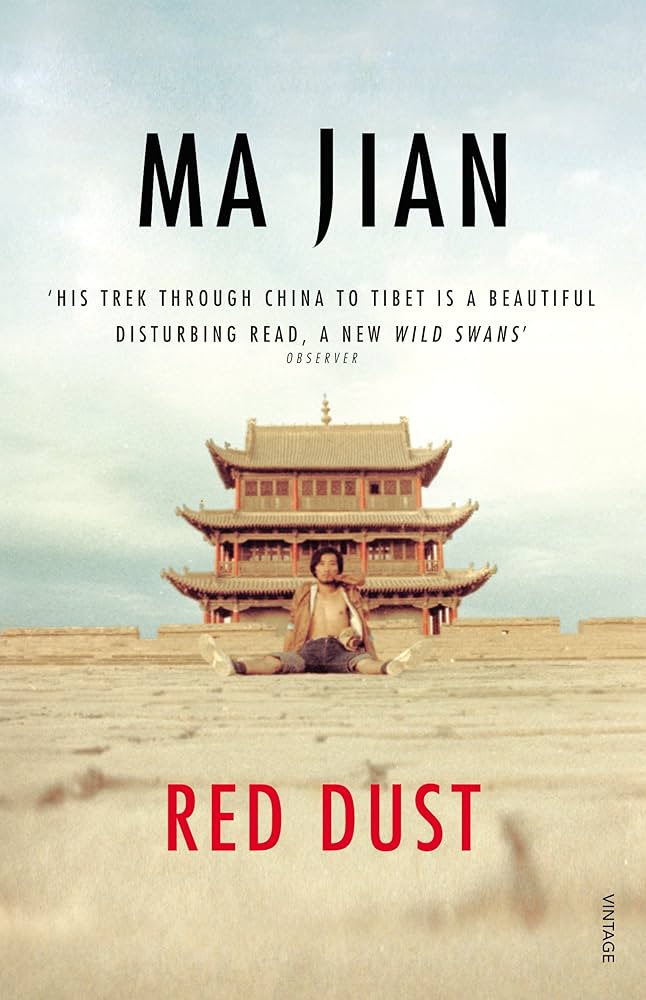

Red Dust: A Path Through China

By Ma Jian

Translated by Flora Drew

(2001, Translated 2002)

Anchor Books

(Novel)

Ma Jian tells a story of self-exile and the peripatetic life he spent wandering without possession and without aim through remote China, Tibet, and Myanmar. His story begins in 1981. He is living with his wife and daughter, working on his art, and trying to figure out what is happening in the art world beyond his neighborhood by hosting secret meetings involving fellow Chinese artists and the occasional foreign journalist. He wins a prize for photography which earns him a position in the foreign propaganda office in Beijing. His marriage ends the following year, and in 1983 he runs afoul of his bosses at the propaganda office and is required to perform a self-criticism. After an evening of drifting through Tiananmen Square and sleeping rough under a painting of Mao, Ma begins to sense the end. Investigations proceed, his art is criticized as negative, bourgeois, and evidence of his spiritual pollution. Friends and family are interrogated, and houses and rooms are searched. After another night in a local jail, Ma decides to walk away from his life, carrying a camera, a flashlight, a compass, 220 yuan, two bars of soap, a change of clothes, and a copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ma describes his lonely odyssey vividly. Motivated in part to reestablish his belief in Buddhism, Ma is a convincing spiritualist. He does not, however, paint himself or the people he encounters as saintly or heroic. He writes with candor about his own failings as a person and as a traveler, admitting that his inability to plan and his romanticized vision of spiritual trekking and sacred lands have led him into yet another disastrous and possibly fatal situation. He laughs at himself often and speaks directly and eloquently of the suffering and cruelty he witnesses while on the road. His tone can be grimly mocking and cynical, but his writing can also sparkle with grace. Ma wanders for three years in search of truth and himself, eventually choosing to return to Beijing and a government that cares not a whit for truth or individuals.

“…In China, where politics is the only religion, people can only find their so-called way in life along narrow, prescribed paths. For me, art is an escape from this, it relieves the boredom and makes life seem slightly more bearable. What a joke! Hauling my paintings around town hoping for some recognition. My inspiration has deserted me this week, every brush stroke feels wooden. My painter friends think I am a diehard conservative, my writer friends think I am a man of loose morals. In Jushilin Temple I am a quiet disciple, in the propaganda department I am a decadent youth. Women call me a cynical artist, the police call me a hooligan. Well, they can think what they like. I only have twenty thousand days left to live. Why bother myself with them? As soon as they talk to me, I get caught and dragged to a place where my thoughts become meaningless and confused, and in order to answer their tedious questions, I have to enter their heads, sit in their brains and politely sip their tea. What a waste of time.”