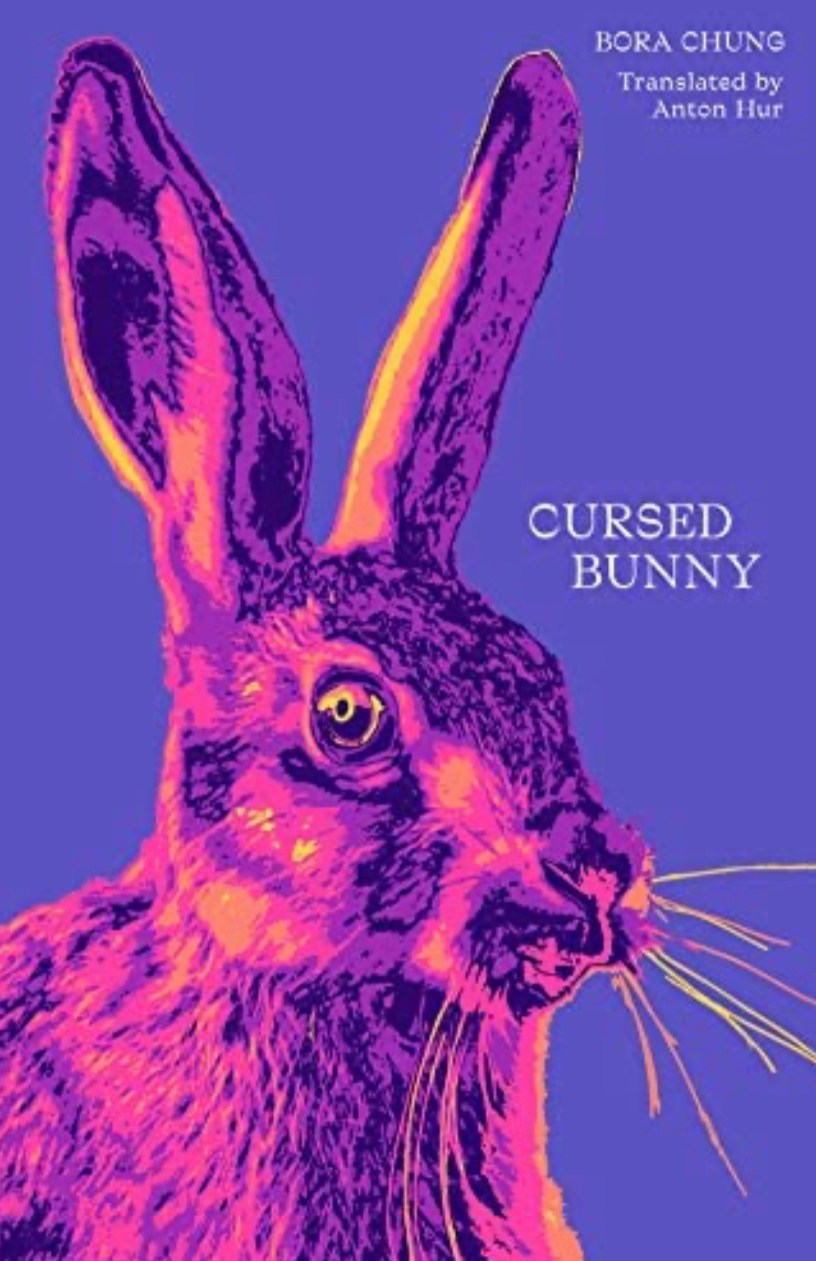

Cursed Bunny, by Chung Bora

Translated by Anton Hur

(2017, translated 2021)

Honford Star

Short Stories

Chung’s Cursed Bunny is a collection of short stories exploring modern South Korea’s wildly obsessive competition for academic clout, high youth unemployment, and masochistic workplace culture, where the South Korean citizens recently voted against the government’s recommended 69 hour maximum work week, up from the previous 52 hours. In 2015, Korean citizens began referring to life in Seoul as the “Hell Joseon” and popularized the term in social media. Many of Chung’s characters are trapped in some kind of hellish world. For example, in “Frozen Finger,” a woman awakes to find herself trapped in her vehicle in total darkness. She has no recollection of the crash, the car is slowly sinking into what appears to be a swamp, and her only chance of escape requires her to follow the disembodied instructions of a woman whose marriage she may have destroyed. In “The Head,” a woman is haunted by a woman who appears in every toilet she uses. The being claims to be made from the waste of everything the woman has consumed and secreted by her body, and it wants to be recognized for what it has endured and given what it wants. In “The Snare,” a greedy man tortures a magical fox that bleeds gold and eventually does the same to his own children in order to raise his social status. In “Scars,” a boy is kidnapped and reared in a cave by a being that violently modifies his body nightly. When he finally breaks his chains and flees this hell, he enters a human society that fears him and promptly sells him into slavery.

In “Home Sweet Home,” a determined woman succeeds in getting out from under debt, sells her home in a good neighborhood, and uses the proceeds to purchase a multi-use four-story building in a backwater. The building’s potential brings out the worst in her neighbors and her husband. After seven years of sacrificing all to finally be free and in her own home, she is surprised by what she will do to keep it. Chung uses elements of East Asian and European folk tales; her surreal fantasy, “Ruler of the Winds and Sands,” might have roots in The Thousand and One Nights. Chung visits the liminal worlds between life and death, both psychologically and physically; some of her more jarring stories address taboos about the body, especially its secret horrors, shame, and guilt.

“She could see the fetus’s movement on the ultrasound but not feel it herself. There wasn’t anything particularly wrong with her otherwise. Aside from telling her to hurry up with finding a father, the obstetrician had nothing much to report. She became so large that other pregnant women felt uncomfortable in her presence. But what did it mean for the baby not to grow “properly”? She thought of the hostile glare of the obstetrician with the thick make-up. If she needed a husband for the baby for its proper growth, what could explain the size of her stomach now?