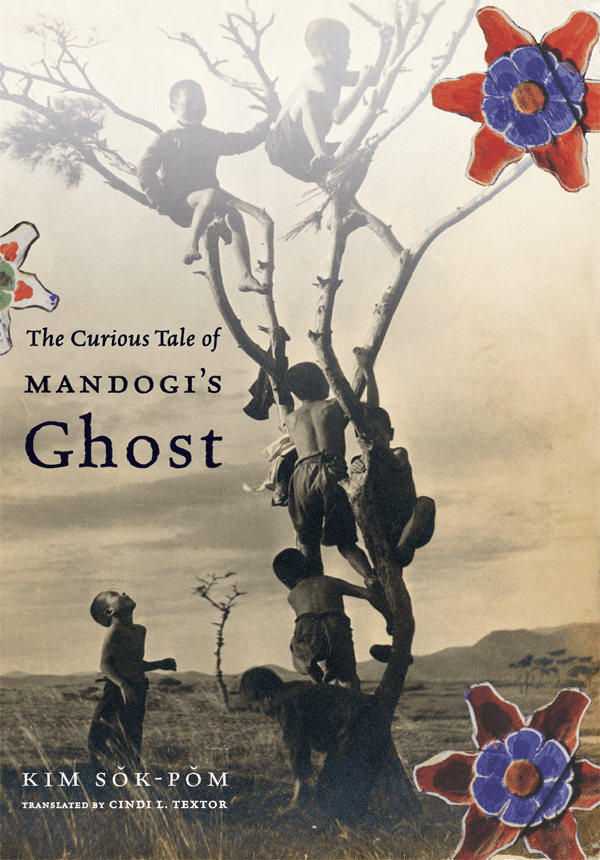

The Curious Tale of Mandogi’s Ghost

By Kim Sok-Pom

Translated by Cindi L. Textor

(1970, translated 2010)

Columbia University Press

Kim Sok-Pom is a second generation Zainichi writer. Elsewhere in this collection, I have grouped Zainichi writers as a subset within Japanese literature. Zainichi are ethnic Koreans who chose to move to Japan or were taken to Japan as laborers during the priod of Japanese imperialism. Zainichi writers typically explore their complicated identity as a minority culture existing within or in spite of the Japanese, their social order, and their legal system. Kim, however, writes mostly about about the experiences of Jeju islanders from the end of World War 2 to the beginning of the Korean War. The inspiration for his interest in Jeju and the 4-3 Rebellion of 1948 is inspired by his parents, who grew up on Jeju Island and took him to visit the island and some of its rebels. Although he moved to Seoul after the Korean War, he continues to live in Japan and write about the Jeju Uprising in Japanese. Kim’s unlikely hero in this novel is temple keeper at a mountain shrine dedicated to Kannon. He stands over six feet tall, but he has the mind of a child, a mishapen smile, and a preposterously large nose. Abandoned at birth, he is literally nameless and appears on no birth register. Locals refer to him as imbecile or Keiton (“Dogshit”). Later, a Budhist priest takes him into the temple and gives him the priest’s name “Mandogi.” And midway through his life he is taken by Japanese to work in a chromium mine, where he becomes legally known as “Mantoku Ichiro.” On his return to Jeju, his beloved temple is dentified as a rebel base and burned to the ground by Korean forces representing Syngman Rhee. For Kim, Jeju is the nut of the Korean problem: an island that had consistentlyand heroically resisted the influence of the Japanese, and a population that identified themselves as citizens of both the North and the South. The Americans aligned themselves with Syngman Rhee and the Jeju Peoples Committee, which became the Workers Party of South Korea in 1946. When the US dissolved the Peoples Republic of Korea and called for general elections in South Korea, which included Jeju, many on the island sympathized with Koreans in the North and vowed to oppose the elections in the South believing that they would be legitimizing the U.N.’s division of the country. Kim places his saintly Buddha in the center of the conflict. But Mandogi is not alone. The U.S. backed police target a young wife whose husband has disappeared. A local captain explains to the woman’s father that he believes the missing man is with the rebels. If that is the case, the police would find it necessary to execute the entire family as “Reds,” unless the patriarch can convince his daughter to marry the captai. This is a tale of extraordinary cruelty. Betrayals are common, and Kim never looks away from the barbarism of Rhee’s forces as they seek to pacify the beautiful and holy island. The Curious Tale of Mandogi’s Ghost is essential reading for anyone interested in the Jeju Rebellion.

“In this country, to become a police officer or a substation chief, no education was necessary. On this island, most of the policing jobs were given to friends of the Northwesst Youth Group, but the majority of them were illiterates who had never opened a book. To be sure, it was a party of ignorants and illiterates, but having been appointed as the highly educated Syngman Rhee’s bodyguards, the Northwest Youth Group was made up of the greatest red-hunting champions in the entire country. In this country, if you could make your enemies look “red,” if you had the violent abilities to wipe the reds, like ghosts, off the face of the earth, then you could easily surpass the educated.”