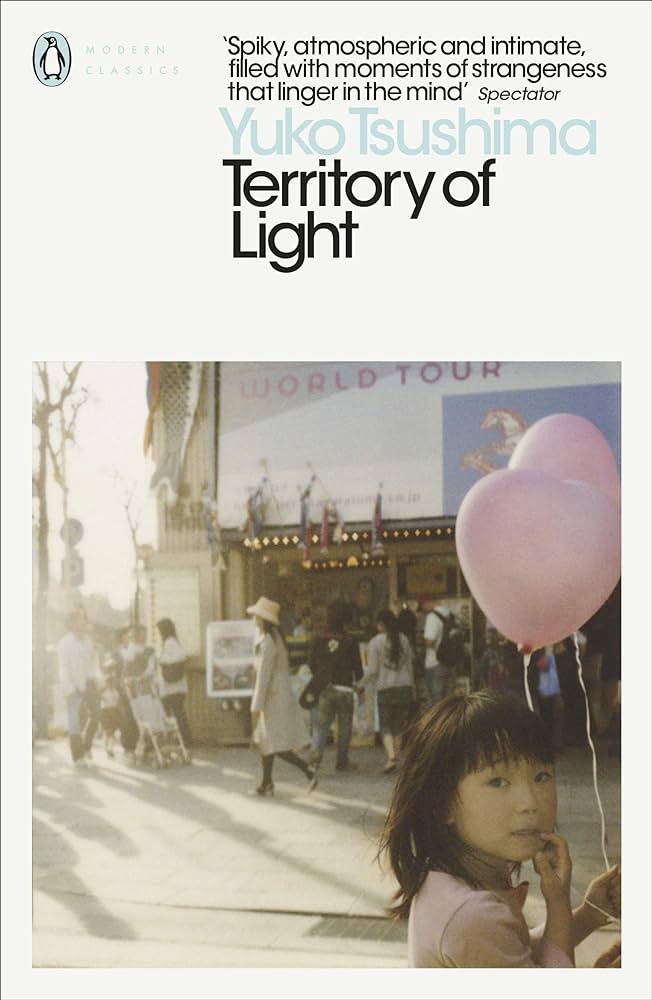

Territory of Light (1978-79)

By Tsushima Yuko (f.)

Translated by Geraldine Harcourt

(Novel)

Territory of Light is a Japanese I-novel first published serially in a magazine between 1978 and 1979. The topic then, and arguably now, was taboo: a young mother describes her efforts to engage her estranged husband in formal divorce mediation. The husband is a hapless, weak-willed, and floundering artist who adopts a grandiose attitude in setting his wife and their child up on their own, though he has neither savings nor job prospects. He appears to waffle between defiantly acknowledging his fault in having an affair and throwing himself on the mercy of his wife. Yet, as much as the heroine struggles to surrender her attachment to her husband, the novel is tightly focused on the mundane struggle to navigate this year apart while keeping her job at the library, getting her child to and from kindergarten, and negotiating crises in their apartment, a light-flooded quasi-industrial space on the fourth floor of a narrow building in a neighborhood that might best be described as of mixed-use. Her independence and separation come at a cost to her and her child’s physical and psychological health. Her identity as a wife and woman unravels and she is forced to consider who she really is. The mother battles a depression that makes it difficult for her to get her child to school and herself to work. She makes awkward social mistakes, lingers among her dreams and nightmares, and takes risks. Her daughter acts out at school and at home; meaning well, the school teachers and principal suggest she get back together with the father for the child’s sake. She drinks, drags a man into her bed, and rides trains past her stop while fantasizing she will never return to her child, yet she also writes about healing moments with her daughter, the persistent kindnesses of friends and acquaintances, and her ability to move beyond the territory of light at the end of a year.

“The man was just a drunk, but his back was broad and hot. The body was a solid one. Its ears were so red, they seemed about to catch fire. My daughter reached out too and we stroked together, four-handed. He wore neither coat nor sweater, having apparently wandered out of doors from somewhere. Intent on stroking the stranger’s back, I found myself drawn into a kind of fervour, as if praying for a miracle.” (138)