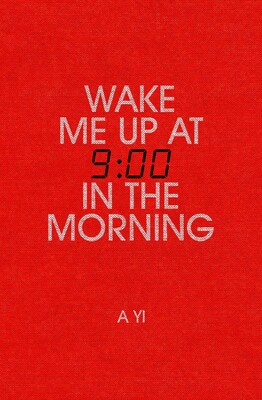

Wake Me at Nine in the Morning

By A Yi

Translated by Nicky Harman

(2017, translated 2022)

Oneworld Publications

A Yi’s Wake Me Up at Nine in the Morning is a complex, unruly, and experimental text that begins with the untimely death of crime boss Ai Hongyang from Aiwan village in Fan Township, Jiangxi province. As news of his inglorious and banal end spreads through the community, characters roll into the village to share their stories of the boss, their own backgrounds, and the favors he blessed them with, as well as a litany of Hongyang’s arbitrary sleights and savage betrayals. The author, a former police detective and journalist and now a professional writer, reveals how the head of the Ai clan controlled the flow of power among the local crime families, police, politicians, his henchmen, lovers, and wife. As a Westerner, I struggled to keep track of the large cast of characters with similar-sounding names; I also had to reread many passages because I couldn’t quite figure out who was speaking. Most of the information we learn about the deceased emerges in stories told by Hongyang’s cousin, the schoolteacher Ai Hongliang, who regales his nephew, Xu Yousheng, with accounts of Hongyang’s brash victories over the local police. For much of the first third of the novel, I wondered by what means Hongyang earned his reputation, so much so that I began to wonder if the people beneath him had created a personality cult. Was Ai Hongyang a genius or merely a manifestation of the people’s desire to live under the influence of a higher power? Who was he, after all? And what held the community together beyond the timely exchange of cartons of cheap cigarettes and alcohol of questionable origin? The novel becomes most interesting in Chapter 16 when an associate from Hongyang’s past seeks him out to confess his fall and make an appeal for protection and guidance. The character is Squint, a petty thief and pickpocket. The two met in a Reform Through Education prison; Hongyang offered him protection, and since then the young man has revered him as a father figure and savior. Drunk, paranoid, and haunted by demons, Squint tells of his escapades with a prostitute named Hook-Pinch and their campaign of theft and murder throughout the impoverished province. This longer episode shines a light on three recurring themes in the novel. The first is that the characters are in a world that offers no opportunities for employment or work sufficient to help them change their economic or social status. Gang life leads to direct access to pocket money and social clout–though true self-reliance and self-determination remain unattainable as Hongyang’s broad foot suppresses all rival gangs and even the police.. Another of A Yi’s themes is how the community compulsively engages in sustaining and exalting the extent of the leader’s influence. His tawdry death does nothing to dampen the impulse of families, peons, and enemies to celebrate Hongyang’s victories and praise him for his largesse. At the heart of these performances of Hongyang’s mythohistorical deeds are his extensions, withdrawals, or denials of guanxi or connections. Finally, as in his novel A Perfect Crime, A Yi continues to wean us off our fascination with “kingpins,” footsoldiers, and their molls. Characters do wax philosophical, but for the most part, A Yi’s characters express their needs, disappointments, and desires in crude, graphic, and often stomach-churning language. Worse, having no power or agency, virtually every man in Aiwan village abuses the women around him. The author portrays Aiwan as a tawdry backwater awash with lazy, illiterate, and morally bankrupt wastrels who posture, preen, and denigrate any women with whom they come in contact. Fans of A Yi’s dark vision of the criminal world and the underside of Socialism with Special Chinese Characteristics will learn much from Wake Me Up at Nine in the Morning.

“Sometimes I’d be afraid of getting back too early and I’d sit on a grassy bank, staring into space. The tarmac road, as ink-black as a bottomless pool, unfurled before my eyes until it reached the horizon, and the cars sped past, growing smaller as they receded. Concrete chimneys of enormous girth reared up at the edge of the road, vomiting one last puff of smoke. Once, a man in uniform came up to me and told me: ‘Idleness is the root of all evil.’ Looking portentous, he snorted out a lengthy stream of smoke, then patted me on the shoulder and left. I was well aware of the truth of his statement. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to change, it was just that I was dragged down by an immense physical inertia. I was dead to the world, as my father used to put it.”