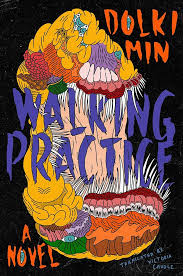

Walking Practice

By Min Dolki

Translated by Victoria Caudle

(2022, trans. 2023)

Harpervia

The narrator in Walking Practice is a refugee who lives in a ramshackle pile of boxes in a forest abutting a national park somewhere on the outskirts of Seoul. Like more and more South Koreans, they live as a hanjok: they live alone, shunning both relationships and marriage. They are paradoxical, however, in that while they are socially awkward and would prefer not to imperil their solitude, they are compelled by an Olympian sex drive to interact, regularly and spectacularly, with countless partners. They accomplish this feat through doom-scrolling through dating apps. Having no car, they message anyone who lives close enough to the subway, and like them, either lives alone or is comfortable meeting at a love hotel. The narrator is difficult to like. They wax rhapsodic about the pleasures and the ins and outs of their and their lovers’ eroticized bodies, but become harshly critical–violently so–should a date be late, slow to answer a door, or ask too many questions. Yet they also speak engagingly about their loneliness and desire to love and be loved. What to do with such a creature? Walking Practice is a queer science fiction novel that speaks candidly and humorously about many of the issues facing the LGBTQ+ communities in South Korea and around the world. South Korean national law does not afford protections to individuals based on their gender or their sexual preferences. Korea also does not recognize same-sex marriage. Like the protagonist of Walking Practice, they are marginalized and struggle with questions of identity and self-worth. Consider this: whenever Min Dolki publicly promotes their book, they conceal their identity with a disturbingly uncanny human mask. The author challenges readers at every step with language that is at times pornographic, bloodthirsty, and monstrous. The main character’s essential difference impacts their ability to put their emotions into words, a breakdown in communication and narration which Victoria Caudle renders physical on the page–if you encounter bizarre kerning and fragmented formatting, don’t assume that there has been a misprint–our narrator is just deep in their feelings.

“Happiness is an incredibly rare and dangerous emotion. I’m someone who can’t bear the fall from happiness to despair. I need a safety net to prepare for it since the higher I climb, the greater my injuries will be when I fall. That’s what’s so frightening. You never know when an iron mace will beat you out of your drunken happiness, casting you into hell. Am I incapable of fully enjoying even the smallest moments of happiness? As soon as I’m happy, I start having ominous thoughts of ruining that happiness.”