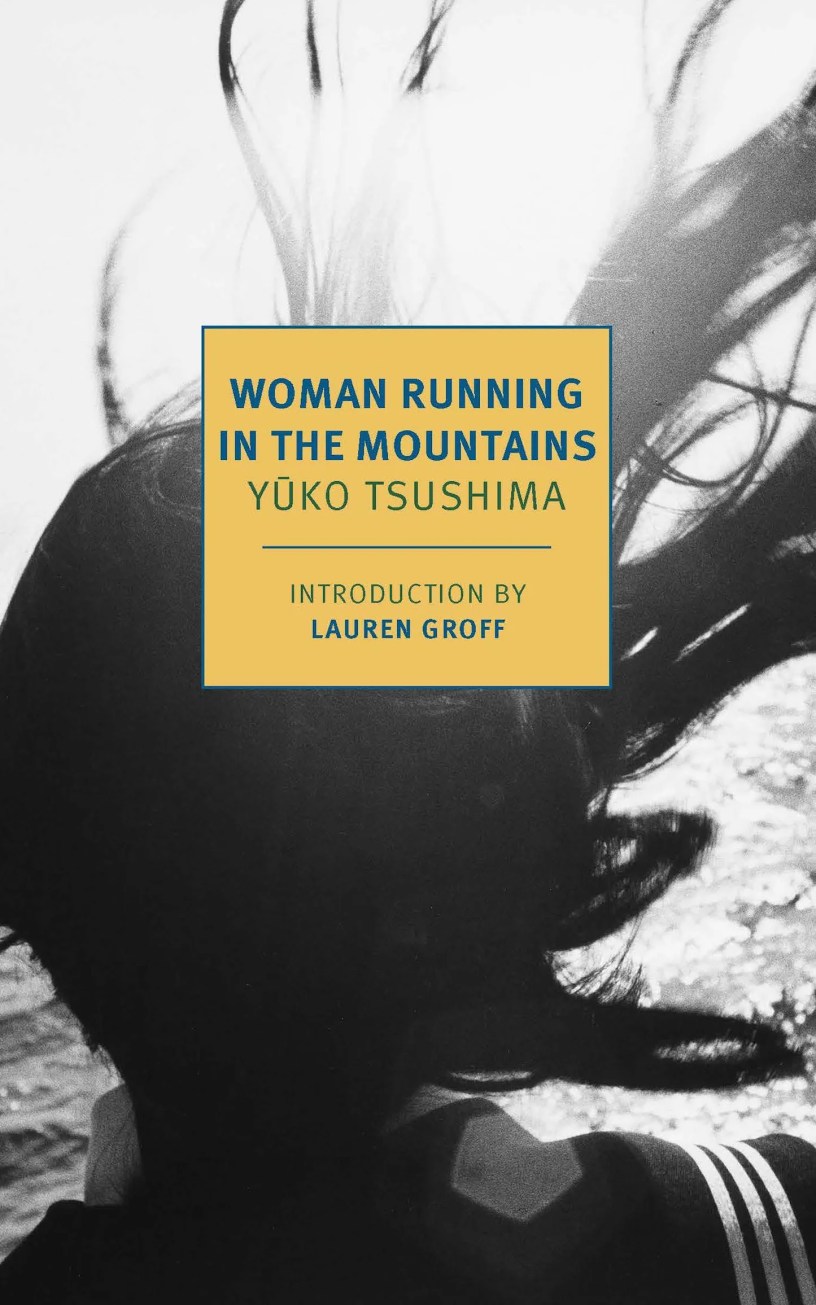

Woman Running in the Mountains

By Tsushima Yuko

Translated by Geraldine Harcourt

(1980, translated 1991, re-released 2022)

New York Review of Books Classics

Tsushima sets her novel in the 1970s in Tokyo. The narrator is Odaka Takiko, a twenty-one-year-old woman who lives with her younger brother Atchan and her verbally abusive mother and physically abusive father. When we first meet her, it is early morning and she is sneaking out of her house carrying a small suitcase. Though the day is suffocatingly hot and she is heavily pregnant, she is determined to walk on her own to the local hospital. Betrayed by a mother who urges her to abort the fetus and promises it will be a deformed monster, and a father who bloodies her nose or bruises her body every night, she is adamant to begin a new life on her own terms. Prior to the birth of a healthy son, Odaka seems to have been a loner, interested in developing friendships or relationships. She lives life moment by moment, a ghost in this world. The father of her child is a married man in his thirties. She did not love him, nor was she attracted to him. As she tells it, he sought comfort and she felt it was her role to meet his needs. She sleep-walked through the affair and did not grieve when he cut it off. At times, she seems to have been in a fugue state. She identifies with a female hero she saw in a Western movie who left her tribe to to give birth to her child in the wilderness and recurring dreams in which she encounters a gathering of indigenous men at work in a snowy landscape. Recovering in the hospital, she spends hours focusing on the beauty of a poplar tree she can just see from her bed. From that moment on, trees and flowers provide Odaka with hope and determination to become a good mother to her son. Real-life confronts her immediately. She realizes her plan to get a job and live apart from her parents depends on finding daycare–a necessity she had never imagined. The search for an affordable daycare with openings is an epic struggle, but once she attains her goal she feels strong enough to seek work. Eventually, she is hired at a plant nursery. The physical labor, the smell of the earth, and the vibrancy of the plants ground Odaka. In the company of her fellow workers, she finds safety and comradery and discovers that between these men and her young son, she is coming alive in a way that is akin to waking up to the world.

“Though she wanted to hurry to avoid the neighbors’ prying eyes, she had to keep her pace slow. She made her way along the street with her shoulders back and head high. In the three months or more since her size had been noticeable, Takiko had never once walked along the alley with her head down. Even on rainy days, when there were puddles everywhere, she hadn’t lowered her eyes. She refused to lower her eyes before “the neighbors”—those people who had made Takiko a sorrow to her mother because her mother cared what they thought… For an instant Takiko closed her eyes and pictured herself holding a baby lightly to her breast and running at top speed. This was the way she had gone on imagining herself, while her mother’s crying and her father’s shouting echoed around her, ever since her mother had found out she was pregnant. At school she hadn’t actually liked running at all, yet now she couldn’t stop seeing this image of herself. It was not that she was running away. She just wanted to be tough and free to move. A state that knew no emotion. To be allowed to exist without knowing emotion.”