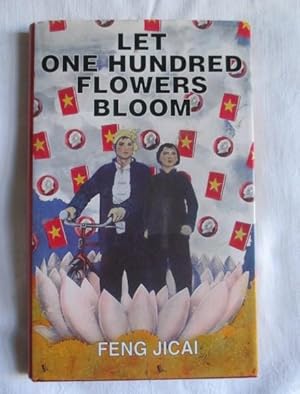

Let One Hundred Flowers Bloom

By Feng Jicai

Translated by Christopher Smith

( , translated 1995)

Viking

Ostensibly a book written to explain to Chinese children the impact of the Cultural Revolution on ordinary citizens, Feng Jicai’s Let One Hundred Flowers Bloom tells the story of the passionate young painter Hua Xiaoyu who is targeted as a rightist and sent down from the Beijing Academy of Fine Arts to the remote Number Two Porcelain Factory in Qianxi county. The story is set at the end of the Hundred Flowers campaign, when Mao encouraged the intellectual class to openly criticise the party in order to improve and butress revolutionary thinking. Mao famously declared: “Let one hundred flowers bloom. Let one hundred schools of thought contend.” At the end of this political exercise, which many believed was a genuine opportunity to praise and reform aspects of the communist vision for China, Mao announced an all-out attack on intellectuals who participated in the Hundred Flowers campaign. Unleashing an anti-Rightist movement, Mao ordered students, professors, writers, and artists to be stripped of their positions and rusticated to remote regions where they would be cleansed of their corrupt thinking by working with those who Mao believed embodied the purest Chinese spirit: the peasant class. Fortunately, the moment he arrives at the remote factory, twenty-year-old Hua falls in love with the art of sculpting, painting, glazing, and firing porcelain and embraces any privations he encounters. He even falls in love and marries. However, when the Cultural Revolution arrives in Qianxi, Hua’s co-workers turn on him. He wakes one day to find his name pasted all over town on the infamous large character posters that sent many innocents to their doom. Jealous workers accuse him of having a Black background and being a Rightist. They imprison him and force him to undergo public self-criticism and physical struggle sessions. After they destroy his home and his art, they send him further into the mountains to quarry stone.

Feng Jicai is himself an artist and advocate for folk art, so it is not surprising that he is at his best when expressing what it is like to be an artist as well as what happens when true artists meet and communicate. Perhaps as a way to engage a young adult audience or add a folk element to Hua’s story, he introduces a loyal dog into the narrative; he becomes the one character in the tale who never fails or betrays his master. A recurring theme in Hua’s account is that he feels no anger or bitterness toward the people who targetted, jailed, and beat him, explaining that every act of the anti-Rightist movement and the Cultural Revolution enabled him to learn more about himself and about the importance of making art. Amazon reports that the Reading Level for this short novel of less than 110 pages is suitable for Grades 7-9.

“The huge courtyard was covered with countless pieces of pottery waiting to be fired in the kilns: bowls, huge vats, bottles, jars, and pots vied with each other for space. The unfired items had an untamed look about them. They possessed a natural and elemental beauty in their rough, unfinished, purple snd white state. All the kiln workers were naked from the waist up, their tough, supple backs burned black by the sun and shining with sweat. The big furnace in the background looked as though it had been painted all over in brick red and golden brown. It was the purest and most glorious blaze of color I had ever seen. Real life colors are always so full of vitality, so fresh. I immediately fell in love with the place.”