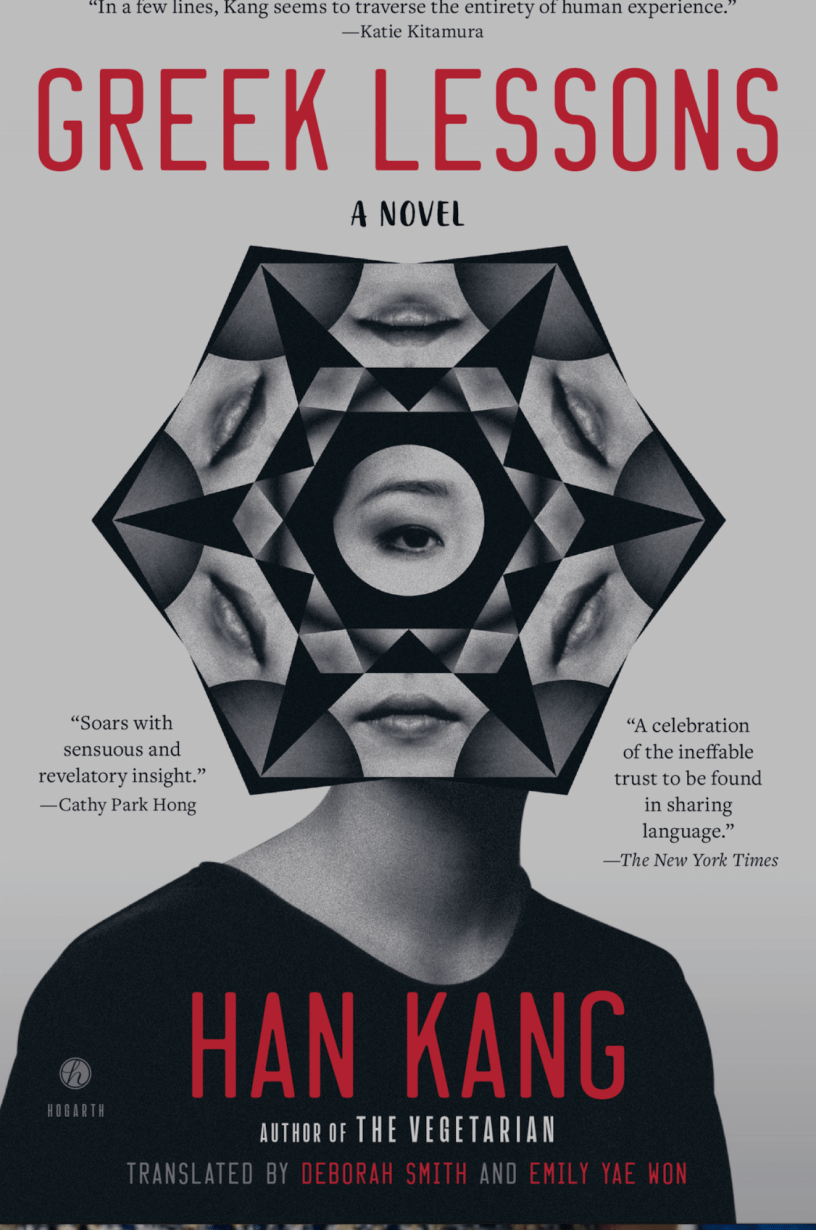

Greek Lessons

By Han Kang

Translated by Deborah Smith and Emily Yae Won

(2011, trans. 2023)

Hogarth

Han Kang’s Greek Lessons is a novel about the Korean diaspora, trauma, and the struggle to make meaningful personal connections in the 21st century where everyone is from somewhere else and home and identity are far, far away in place and time. The main characters are singletons and nameless. The male lead is an academic, who, in another era, might have been comfortable as a monastic or an itinerant preacher. He is a lecturer at a university, a researcher and linguist who meets weekly with a handful of others drawn to read Greek poetry. He speaks in the first person. The female lead is a Korean national. Her mother has died recently and her marriage has dissolved. Unbalanced by these losses, she struggles financially and mentally to take care of herself and her young son–so much so that her ex-husband files for sole custody of the boy and wins. Utterly bereft, she becomes mute. As she begins to get back on her feet but is unable to speak, she decides to take a language course, hoping it will cause her to reintegrate her feelings and speech. Han provides us with compelling flashbacks into the lives of the teacher and student. We learn, for instance, that he has his own fraught family history, and he is losing his sight and will very likely soon be blind. Out of the corners of our eyes, we see bits and pieces of the other students, odd fellows who are taking time out of their lives to master a dead or at least moribund language. The heart of this short book (160 pages) consists of the silent woman’s ruminations on the nature and purpose of language. How do thought and language, with their manifold orthodox and unorthodox collections of meanings, grammar, and punctuation construct us? What common perceptions and civil order must exist for us to communicate our needs and express our feelings? In some ways similar to Han’s The White Book (2016), a catalog and celebration of the gift of grieving, Greek Lessons is a love song to the elusive and incandescent quality of language and our drive to find who we are and what we feel in the language we speak.

“When she was still speaking, she would sometimes simply fix her eyes on her interlocutor, as though she believed it was possible to translate perfectly what she wished to say through her gaze. She greeted people, expressed thanks and apologized, all with her eyes rather than words. To her, there was no touch as instantaneous and intuitive as the gaze. It was close to being the only way of touching without touch.”

“Language, by comparison, is an infinitely more physical way to touch. It moves lungs and throat and tongue and lips, it vibrates the air as it wings its way to the listener. The tongue grows dry, saliva spatters, the lips crack. When she found that physical process too much to bear, she became paradoxically more verbose. She would spin out long, intricate sentences, shunning the vitality and fluidity of easy conversation. Her voice would be louder than usual. The more people paid attention to what she was saying, the more abstract her speech became and the more broadly she smiled. When these instances recurred at frequent intervals, she found she was unable to concentrate on writing, even when she was alone.”