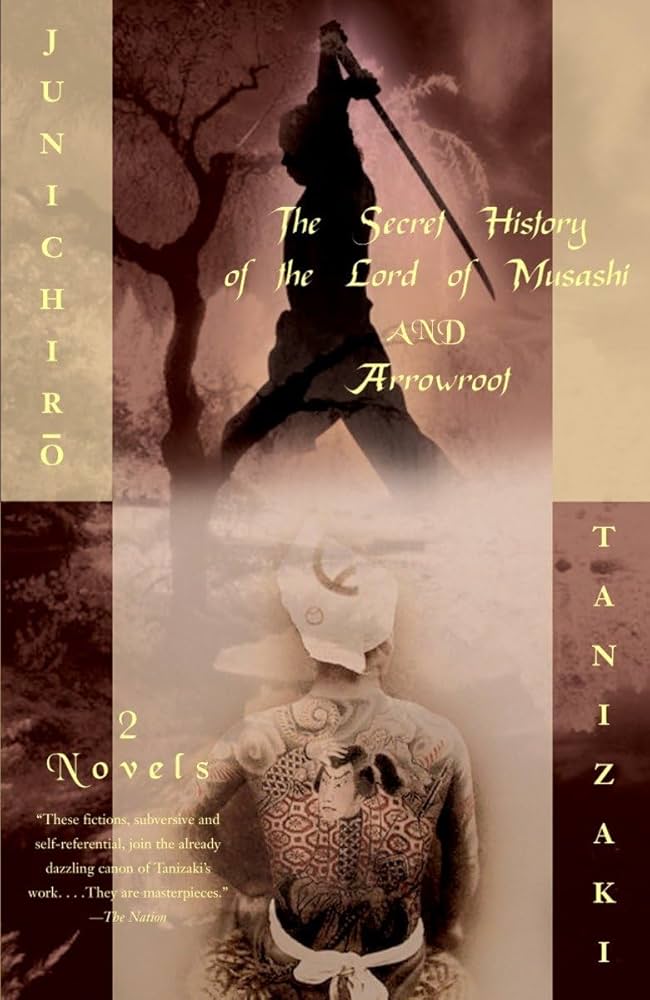

The Secret Life of the Lord Musashi and Arrowroot

By Tanizaki Junichiro

Translated by Anthony H. Chambers

(1935, 1933, translated 2003)

Knopf, Doubleday Publishing Group

Tanizaki published The Secret Life of the Lord Musashi in 1935 and Arrowroot in 1933. Presented together by Knopf Doubleday in 2003, they are exemplars of an artist at play with traditional narratives, court romances, classical historical novels, folklore, classical dramas, and the academic and amateur readers who become obsessed with them. In The Secret Life of the Lord Musashi, Tanizaki parodies court romances while also skewering the narrator’s fascination with achieving his own fame through establishing apocrypha (and perhaps his own fantasy) as historical fact. The overeager scholar claims to have unearthed a lurid and previously unknown tale of the young warrior, his rise to power, and the woman he chooses to serve as his inspiration. What arouses the young samurai’s ardor is both unspeakably grotesque and absurd, something akin to what might be found in “In Spring, In the Woods Under Cherry Blossoms in Full Bloom,” by Ango Sakaguchi and Gogol’s portraits of madness. As the story becomes more and more outlandish and his muse begins to outmaneuver and elude him, the overheated narrator doubles down on the authenticity of his tale, bracing it with detailed but almost certainly spurious references and footnotes. In a similar vein, Arrowroot recounts a writer’s search for inspiration for his tales in legends and local folklore. Hoping to write a historical novel about the period of the Northern and Southern Courts, he becomes intrigued by reports of people in a remote valley who claim to be descendants of members of the Southern Court who evaded capture and death. The narrator heads off in search of the descendants of the ancient heroes as well as any historical artifacts or documents that would establish the credibility of their claims. He is joined by another writer who helps him process his investigations as well as his attempts to make his discoveries align with historical facts. As obsessed as the narrator is to derive a sense of certainty from relics and word-of-mouth testimonies, he almost misses a contemporary romance when his pragmatic, level-headed second leads the narrator to the gate of a woman and a love affair worthy of recording.

“There was no point in telling him when the Gembun Period was, or in citing The Mirror of the East, or The Tale of the Heike on the life of Lady Shizuka. For him she was a noblewoman who symbolized the days of distant ancestors, the cherished past. The phantom aristocrat called “Lady Shizuka” was the focus of his reverence and devotion for “ancestors,” “lord,” and “antiquity.” There was no need to question whether the noble lady had sought lodging in this house and lived in loneliness. It was best to leave him with the beliefs that were so important to him.” – from Arrowroot