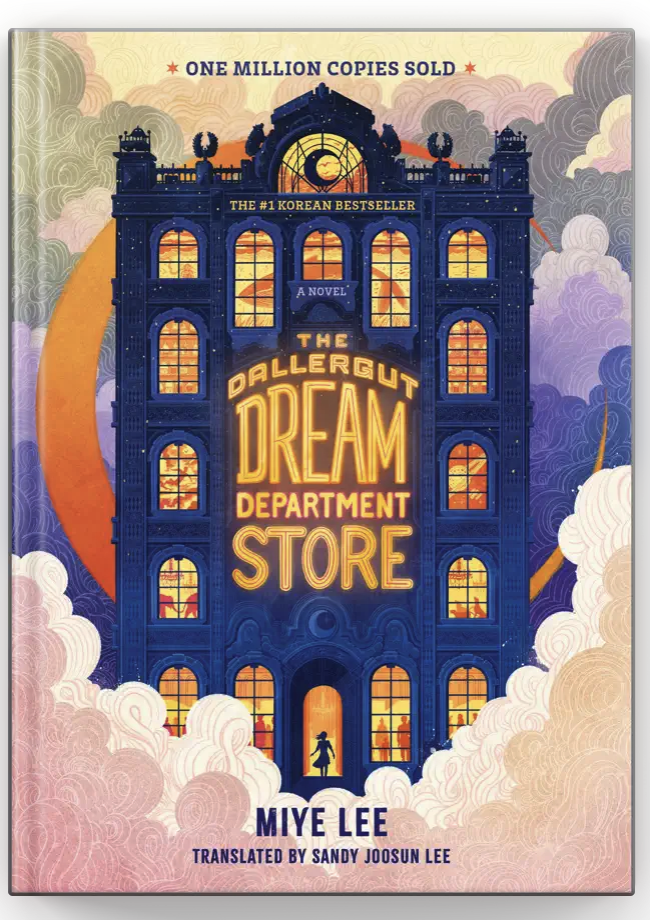

The Dallergut Dream Department Store

By Lee Mi-ye

Translated by Sandy Joosun Lee

Hanover Square Press

2024

Lee Mi-ye’s The Dallergut Dream Department Store joins the ranks of recent South Korean novels that are born on the internet, garner a wide following, and are bought up by publishing houses and sold as physical books, such as the memoir I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki. It is also a recent entry in the growing trend of Korean “Healing Fiction,” which feature protagonists, who, having suffered a trauma or who are reconsidering their careers or the type of life they want to live, embark on challenging quests of self-discovery that are almost always rewarding; Hwang Boreum’s Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookstore is a recent exemplar of this highly popular genre. In The Dallergut Dream Department Store, a young woman, Penny, finds herself in a small town in a city populated by the spirits of sleeping dreamers. Perpetually looking for work, she is ecstatic to be offered a job at the front desk of the Dallergut Dream Department Store, one of the town’s many retail shops that sell “off the rack” and “custom made” dreams to the pajamaed and beslippered shoppers who wander into their store. Each chapter features either an episode of Penny’s on-the-job training, a study of the handful of Dallergut’s most popular dream designers, or a glimpse into a client’s dream experience. The motivations of these shoppers – the dreams that lie behind the dreams they choose are profoundly moving. The dream designers are, for the most part, focused more on profit than art, though there are a few stand-outs (keep an eye out for the man who designs dreams for animals). Penny is engaging, full of wide-eyed admiration for the shop and its master, acutely sensitive to the needs of the dreamers, and an eternally sympathetic audience for their dreams. She is an eager to please, almost desperate to please employee. She is also altruistic and naive to a fault. She makes a colossal mistake in her first week at work, but Dallergut merely explains her error, how she was duped, and the financial consequences to be suffered by the store. At no time does he berate, shout at her, or threaten her with dismissal; he simply moves on with his day. That early interaction sets the tone for the novel and reveals why South Koreans are buying this book: it offers an alternative to the unsatisfying, exhausting, and often dehumanizing reality of so many young people who are trying to start their careers and work their way up in an over-saturated job market. Lee’s The Dallergut Dream Department Store offers the unemployed and the newly hired a cup of tea and a warm blanket for those battered by the cutthroat and often cruel work environment that hides behind the shiny glass in Seoul’s office buildings and corporate towers.

“At first glance, the second floor looks clean, without a speck of dust. A simple wooden interior and evenly placed lighting fixtures. Even the product tags look as consistent as clockwork. Most of the display stands are empty, but the few items still in stock are placed at exactly the same angle, each with the same ribbon tied to them. The employees in their aprons walk around the display stands, conscientious and anxious as they look after the prospective buyers, who inspect various products and put them back in a disorderly fashion.

While the first floor sells only a handful of high-end, popular or limited-edition, preordered products, the second floor sells more generic dreams. Also known as “The Daily” corner, the second floor displays dreams of simplicity. Dreams of quick getaways, hanging out with friends, and enjoying good food.

In front of the staircase where Penny stands is a display case marked Memories. Inside it is a luxurious leather case labeled No Refund Once Unsealed. Only a few dreams remain.”