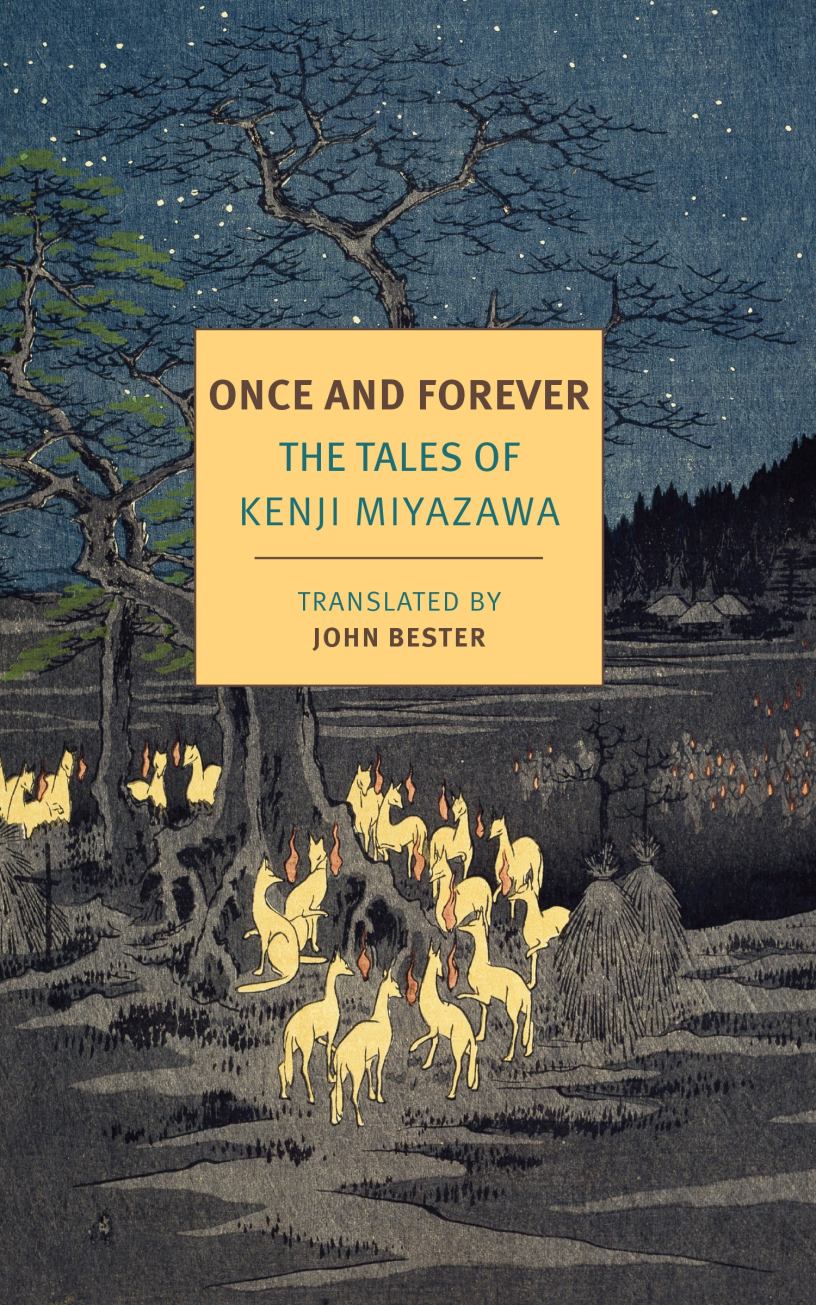

Once and Forever: The Tales of Kenji Miyazawa

By Kenji Miyazawa

Translated by John Bester

(Circa 1918, translated 2018)

New York Review of Books

Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933) was a novelist and poet. He lived in Iwate, the son of rice farmers and the owners of a pawn shop. Their success allowed them to hire teachers from the Pure Land Sect to use their home as a base for teaching and the exchange of ideas. Miyazawa was attracted to the world of the peasant farmers and the natural history of his environment. He also grew apart from his parents. In high school, he converted to the Hakke sect of Buddhism and went on to pursue a degree in Agriculture and Forestry. He became a member of the Kokuchai and went to Tokyo to proselytize Nichiren Buddhism, which combined religious piety and fervent nationalism. He expressed interest in becoming a priest, but he was convinced that he could serve the world better by teaching modern agriculture to the peasant farmers of Iwate. Miyazawa wrote hundreds of tanka and experimented with prose poems. He also wrote a significant number of children’s tales inspired by local folklore, Shinto beliefs, and the Buddhist tradition. His most famous poem, Ame ni mo Makezu, “Be Not Defeated by the Rain,” was adopted as a clarion call by the Nichiren Buddhists who discovered the poem after his death; biographers and scholars of Miyazawa’s works argue that the writer split from this group after growing disillusioned with their nationalistic beliefs. None of Miyazawa’s works were popular in his lifetime, yet a steady stream of authors count Miyazawa as an inspiration, and several of his children’s tales have served as source material for popular anime films. This collection, curated and translated by John Bester, features twenty-four short stories. Standouts include the prose poem “General Son Ba-yu,” a tale of a Chinese warrior who returns from thirty years patrolling the deserts beyond the Great Wall only to discover that he has fused with his ancient horse and can not dismount; “Gorsch the Cellist,” about a ham-fisted musician whose ear and skills are transformed under the tutelage of a variety of birds; “The Red Blanket,” in which the Old Snow Woman battles Snow Boy for the life of a lost child, and the surreal “March by Moonlight,” where a trespasser discovers the inexorable nightly advancement of thousands of anthropormorphic telegraph poles along Japan’s rural railroads. Once and Forever is essential reading for anyone interested in values, spirituality, and folklore of early 20th century Japan.

“General Son reined in his horse, raised a hand in a lordly way to his forehead, peered hard to make sure what it was, then suddenly saluted and hastily made to dismount from his horse. But he could not get off. His legs seemed to have become fastened to the horse’s saddle, which in turn was stuck firmly to the horse’s back.

The stouthearted general was greatly dismayed despite himself. Turning red in the face and twitching his mouth up at one side, he did his utmost to leap off his mount, but his body refused to budge. Poor general: as a result of thirty long years spent doing heavy duty on the nation’s frontiers, in the dry air of the desert, and without ever once dismounting from his horse, he had finally become one with it. What was worse, since not even grass could grow in the middle of the desert, the grass must have chosen the general instead, for his face and hands were covered with some strange gray stuff. It was growing on the soldiers, too.

In the meantime, the king’s representative drew gradually nearer; already the great spears and pennants at the head of his party were visible. “General, get off your horse!” said someone in the ranks.

“It’s the messenger from the king! General, off your horse!” But though he flapped his arms about again, he still could not get free.

Unfortunately, the minister assigned to welcome him was as shortsighted as a mole and thought the general was deliberately refusing to dismount and was waving his hands as some kind of order to his men.

“Turn back!” cried the minister to his party. “It’s an insurrection!” And promptly wheeling their horses around, they all dashed off in a cloud of yellow dust.”