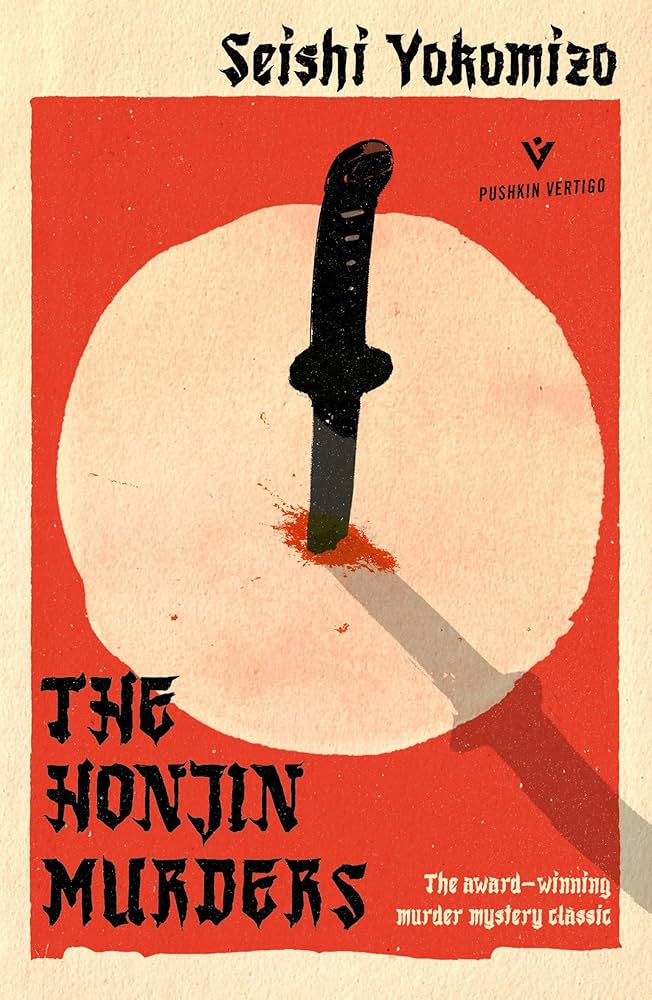

The Honjin Murders

By Yokomizo Seishi

Translated by Louise Heal Kawai

(1946, trans. 2020)

Pushkin Vertigo

Houseki magazine published The Honjin Murders in serial form in 1946. Yokomizo presented his audience with a hankaku, a locked door mystery, a “pure” and “purists” genre which dominated Japanese popular fiction well into the 1960s. Awash in imitations, writers, connoisseurs, and philosophers policed the genre, rewarding invention, economy, and logic while excoriating works relying on gimmicks and sophistry. Yokomizo’s narrator, a chronicler of of 20th century crime, regales us with a tale of a double murder in a rural village in Okayama: a recently married couple is found slaughtered inside a locked room. To complicate matters, there is no weapon in the room, though police discover a samurai sword in a nearby garden. We learn about the family history of the owner of the home, the father’s relationship with his son, and the unique architecture of the honjin, a traditional stopping off place for a high-ranking samurai, and in that time, the permanent home of a local official. The case is so exceptional that the narrator concludes the only chance for justice is to send for an old friend. For fans of the hankaku genre, The Honjin Murders greatest significance is that this is the first time Yokomizu introduces his humble, distracted, and soon-to-be iconic detective, Kōsuke Kindaichi. At the start of his journey into the genre, Yokomizo is eager to establish his bona fides as a mystery writer, not only nodding to European and American fictional detectives, but also introducing the brother of the murdered man as an amateur sleuth who prides himself on his extensive library of the scientific analysis of crime and physical copies of the international canon of crime fiction. Despite that almost comically weighty cloud of Western literature, Yokomizo introduces his hero with confidence: disheveled, plain-spoken, and direct, he converses with all people in the highly stratified world of post-war Japan without judgment or bias. He is an active listener; patient, sympathetic, quick to acknowledge his confusion, and devoted to preserving human life. While the impenetrable puzzle of the locked room crime and the brutality of the murders cause the survivors to embrace local lore and the supernatural, Kōsuke follows every lead, either traveling by train to research family documents or calling in favors to old friends in law enforcement and medicine. Fans of Yokomizo will find early evidence of his interest in linking music to mystery and violence as well as his enthusiasm for invoking the gothic and the grotesque. Indeed, Kōsuke encounters more than his share of mutilated and scarred characters in his many adventures (he appears in seventy-seven novels!) and Yokomizo never fails to wring every last drop of revulsion and empathy for those whose suffering is written on their bodies. They are shamed and shunned for their wounds, as is the three-fingered man whose appearance ushers in the horrors of this novel. So many crimes on innocent bodies; should it surprise us that the narrator reveals that he first encountered reports of the Honjin murders after being evacuated from to Oyokama to escape the bombing of Tokyo?

“To me, the most captivating element of this case was the way in which the traditional Japanese string instrument known as the koto was connected from beginning to end. At all the critical moments, its eerie music could be heard. I, who have never quite escaped the influences of romanticism, still find that incredibly alluring. A locked room murder, a red ochre- painted room and the sound of the koto… all of these elements are so perfect—too perfect—like drugs that work a little too well. If I don’t hurry to get it all down in writing, I fear their effects may start to wear off.”