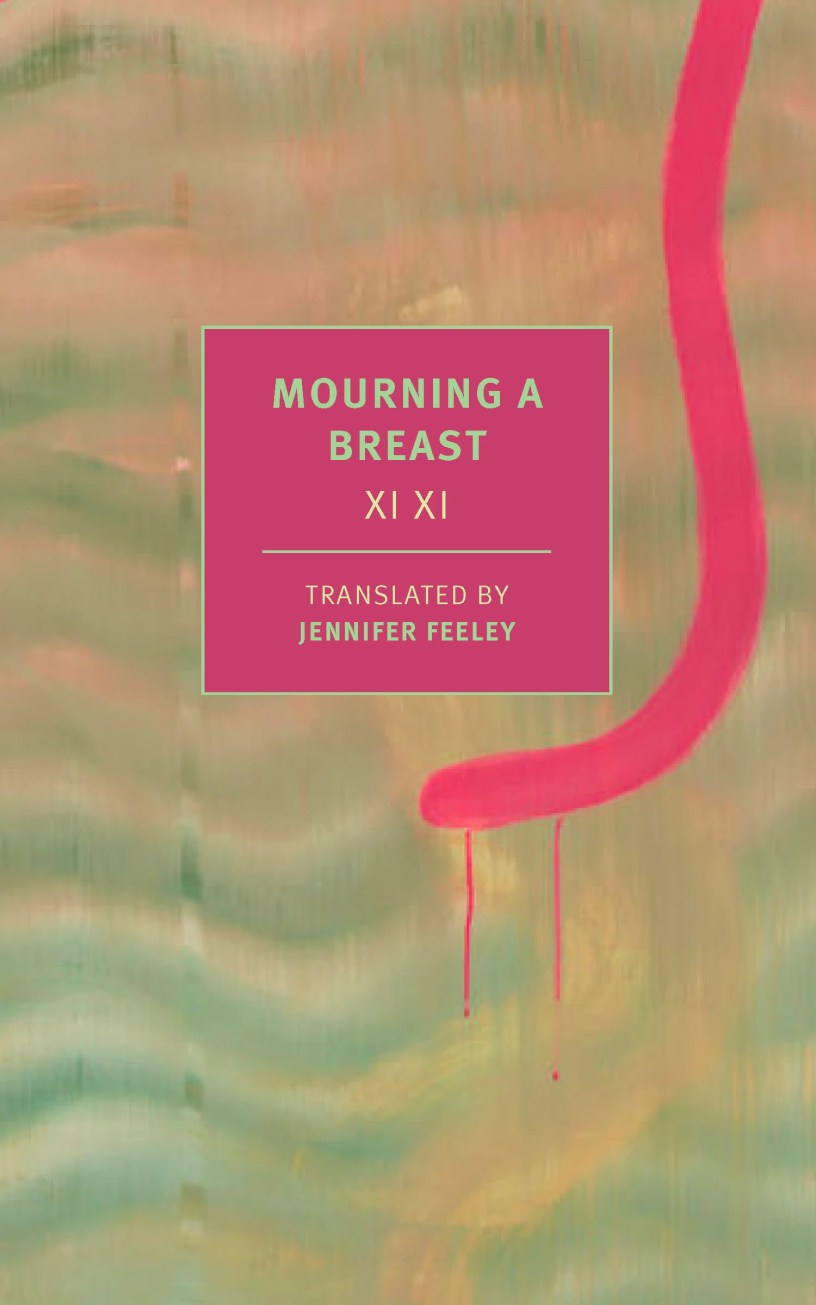

Mourning a Breast

By Xi Xi

Translated by Jennifer Feeley

(1992, translated 2022)

New York Review of BooksXi Xi, also known as Sai Sai, was born in Shanghai in 1937. At the age of twelve, Xi’s family moved to Hong Kong where she studied Education and became a well-known and popular teacher. She established herself as a successful poet, edited and published an influential literary magazine, and became well-known for her essays on film and art. She wrote several screenplays and was involved in China’s avant-garde cinema. Although she is remembered for her short stories and novels, few of her works have been translated into English. Mourning a Breast is Xi’s account of her years-long battle with breast cancer, which began with her diagnosis in 1989. When published in 1992, Mourning a Breast made history as the first Chinese work by a female breast cancer survivor. Though partly fictional, Xi writes with remarkable honesty about her experience, reflecting on how little she knew of cancer, the preconceptions and biases she harbored about people who got cancer, and how she came to be a middle-aged woman with only a superficial understanding of human health and her own body. Her story is compelling, but equally fascinating is the way she interweaves so many allusions from literature, music, art, and Chinese mythology and history. For example, the narrator tells us that she took four copies of Madame Bovary to the hospital to occupy her while awaiting and recovering from surgery: the original French, an English version, and two Chinese translations. She tunnels deep into language, dwelling on Flaubert’s use of italics to signify shifts in narrators, then quickly turns to the forms of narrative in European filmmaking and the degree to which some writers seem to have anticipated cinematic storytelling before the invention of the camera. Her deep dives into her areas of expertise reveal her broad base of knowledge and her acute focus on language, while also exposing how she escapes from the anxiety, uncertainty, and discomfort she experiences. Xi describes her communications with doctors and nurses in fine detail, finding them caring and ready to explain the purpose of visits, procedures, and treatments. She also introduces us to her friend group–an essential resource–especially as she is unmarried and the primary caregiver of her ailing mother. We also meet Ah Kin, who seems like an invention, a composite of the many cancer survivors she met who, like angels, guided her through the harrowing and the banal. Many chapters are focused entirely on health, diet and exercise. Xi goes into great detail describing appropriate calorie intake and healthy foods, while also discussing the pros, cons, and philosophies of traditional Chinese and Western medicine. She also discusses how her illness impacted her love for swimming and the joy and health benefits she has in practicingTai Chi and Tai Chi sword routines. Xi Xi, ever mischievous and candid, acknowledges that she presents the reader with a potpourri of genres and advises the ahead of time and at the end of every chapter which sections contain essential knowledge for women with cancer, as well as which are scientific, philosophical, didactic, and linguistic. There are even chapters that appear to be shamanic in nature, such as “Thrice Striking the White Bone Demon” and dictionary-like, in that they introduce the reader/cancer survivor to the specialized language of the disease, knowing that this new world will require unimagined ways of expressing what they are experiencing.

“My body began to speak more and more frequently, protesting a host of injustices, as though a revolution had begun inside me. Was it staging a strike? Requesting some time off? Fighting for special allowances? I had no clue what its demands were. Our past attempts at dialogue hadn’t gone all that well, and now I could only be subjected to its lectures. Yet the problem remained: What exactly was it saying? Was my white blood cell count too low? Was I deficient in vitamins or minerals? Communication between people is difficult, but talking to the body is even more challenging. There are so many parts, each with its own grievances, the body’s language split into distinct regional dialects. Bones speak the language of bones. Muscles speak the language of muscles. Nerves speak the language of nerves. Ever since humans built the Tower of Babel, we’ve barely been able to converse with one another anymore.”