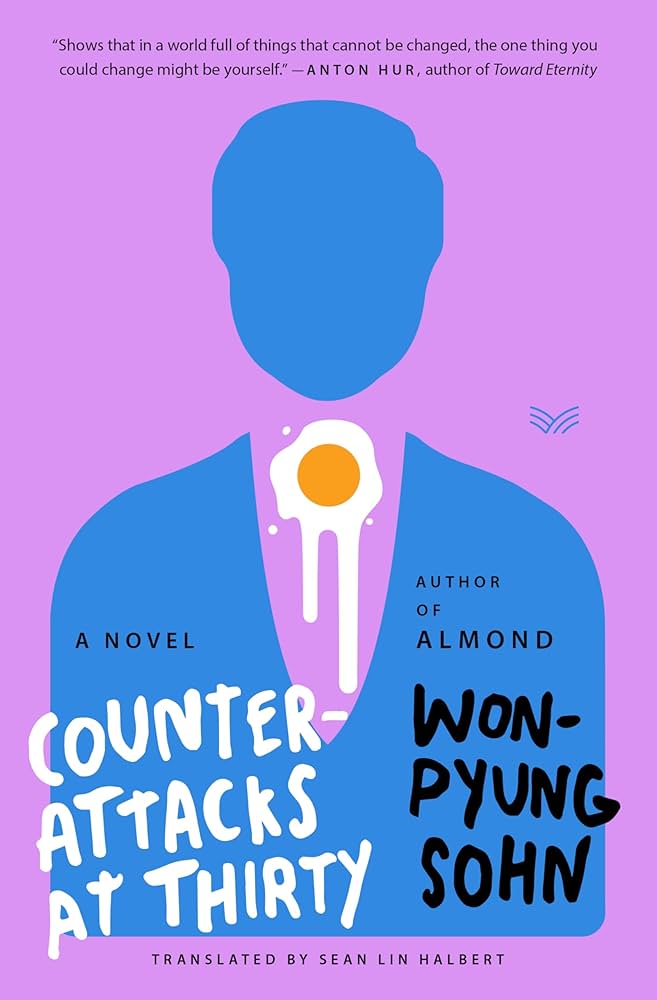

Counterattacks at Thirty

By Sohn Won-Pyung

Translated by Sean Lin Halbert

(2017, translated 2025)

Harper Via

In her novel, Almond, Sohn Won-Pyung introduced readers to exceptional individuals: a boy with an underdeveloped amygdala who is frighteningly unresponsive to danger and pain and nearly incapable of displaying or responding to emotions, and another boy unable to control or understand the consequences of his violence. In Counterattacks at Thirty, Sohn turns her attention not to the outliers but to the generation of Koreans born under the regime of former general Roh Tae-woo, a supporter of Chun Du-wan, who came to power in the military coup of 1979 and who commanded the military to murder Koreans during the Gwangju Democracy Uprising. Sohn’s generation was shaped by a politics of fear, dreaming of finding a place in society where they could work a steady job and live a circumspect and safe life. Her heroine, Kim Ji-hye, is the embodiment of the “880,000 Won Generation,” a cohort of college-educated citizens doomed to live at the bottom of the pay scale, earning approximately $650 a month while working as temps and interns. When we meet her, she has been working for months beyond a period where she was told she would either be let go or become a full-time employee. Her employers, in addition to exploiting her, are in the business of offering education-adjacent classes for post-college adults who, despite all possible social and economic disincentives, remain interested in the liberal arts. Ji-hye, who spends her days making copies and doing coffee runs, sees through the company’s cynical business plan, but even she finds the courses appealing and soon begins taking beginner ukulele courses after work. A loner with an imaginary boyfriend, she becomes drinking buddies with a group of men she met at work and ukulele class. As they share their career frustrations, their talk turns to the inequities of society. Gyeok, who catches Ji-hye’s eye when he calls out an ethically bankrupt professor, suggests they embark on a campaign to shame public figures who have escaped consequences for their transgressions, and thus they begin their counterattacks, acting out in harmless and ultimately futile critiques of Korean society. In Almond, almost every action was extreme and often ultra-violent. In Counterattacks at Thirty, the characters’ efforts to “make revolution” are tentative. They are unsure of themselves before, during, and after their escapades, and with each prank, they will forever remain round pegs in a square world. As in life, characters vacillate, act by not acting, and sabotage themselves. They reveal secrets about themselves and cheer each other on. Sohn captures the spirit of paralysis of this generation, though at times she offers cultural antidotes, balms that are clearly informed by her degrees in sociology and philosophy. Too on the nose, these fantasies are merely distractions in a world where individuals yearn to be creative while only ever having the opportunity to reproduce or purchase the banal.

“Even though this all happened around the time of my birth, I knew it like I experienced it firsthand. The rest of his story–the protests, the fighting, the bloodshed in the square–were nothing to me but tales from long ago, things I had to learn through books and documentaries. Since then, the world has taken a few steps in the right direction, but only a few. Injustice is still the law of the land, and the promised era of ordinary people never came. What we got was the exact opposite: a world in which ordinary people are forced to follow the crowd while simultaneously being expected to stand out from it, desperately screaming from the tops of their lungs, begging to be noticed.”