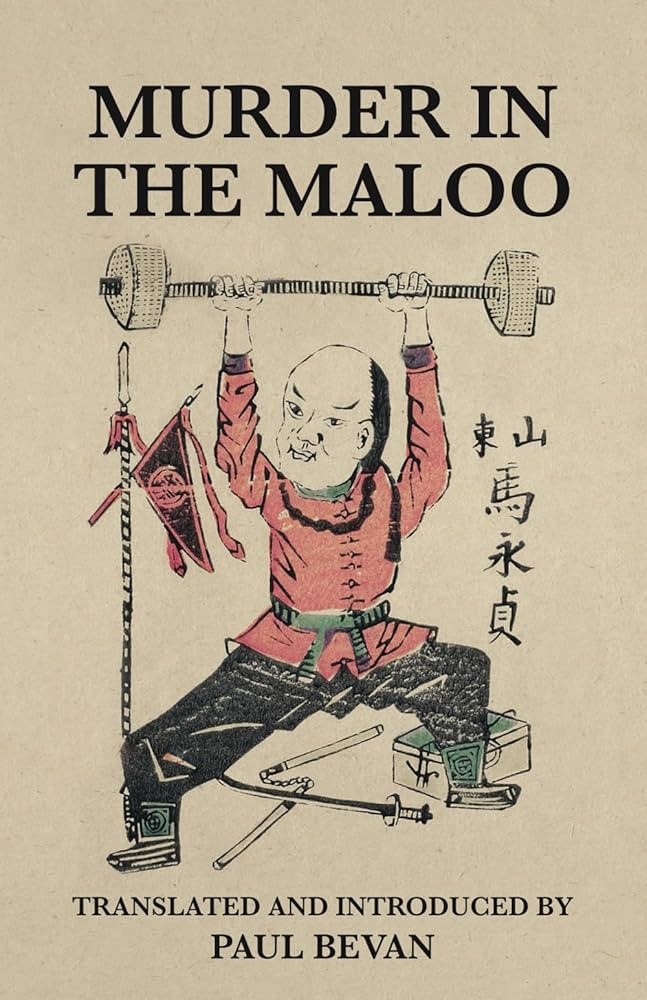

Murder in the Maloo: A Tale of Old Shanghai

Attributed to Qi Fanniu and Zhu Dagong

Translated by Paul Bevan

1923, translated 2024

Earnshaw Books

Murder in the Maloo, a tale of 19th-century derring-do, hard riding heroes, and skulking gang bosses was originally published as Ma Yongzhen: An Historical Romance. Ma Yongzhen was indeed an historical figure who was murdered in Shanghai in 1879. Rendering his story as a romance, the two authors amplified Ma’s moral excellence and his physical prowess, presenting a leader who emerges from the Northern wilds embodying the attributes of an older and purer China. He and his men bring a collection of extraordinary horses into the city to trade, and there they clash with disrespectful and false-dealing gangs. The novel features exciting descriptions of horse racing, which allows Ma and his men to demonstrate their skill as riders and acrobats, as well as the strength, endurance, and courage of their northern steeds. While Ma speaks with honor, the gang leader insults the horses, spreads false rumors, and low-balls his offer. Fights ensue and fists fly. Tea houses and brothels are the scenes of negotiations, brawls, and scheming. In the second half, Zhu Dagong injects energy, muscle, and humor into the writing; the trash-talking soars to new and laugh out loud heights. Murder in the Maloo, with its sequel, The Adventures of Ma Suzhen, in which the hero’s sister arrives in Shanghai to avenge her brother’s murder, enshrined the Ma family and their heroism in the popular imagination. A theatrical version appeared in 1923, and the story of the Ma family became a wildly popular film in 1927, serving as the seed bed for countless martial arts films to come. Murder in the Maloo is a prime example of the “Mandarin Ducks and Butterflies” genre, a form of popular fiction offering an entree into exciting worlds, adventure, and love. Modern readers who grew up on the wuxia epics of Jin Yong are likely to find the tale old fashioned in style and language, and the climactic battle catastrophically brief– and if possible– both tragic and petty. And yet I am eager to learn how his sister will avenge her brother! Finally, if you are familiar with literary masters of the May 4th Movement and The New Culture Movement like Lu Xun and Hu Shih, remember that they were writing during the time of and in opposition to the escapism of the “Mandarin Ducks and Butterflies” genre.

“Tell me, does that opium fiend go by the name of Cheng?” Scrofulous Bai asked inquisitively. This was confirmed by Lu the Lackey. “And he’s the all-knowing big boss of the Zhengjia Wood Bridge district. Is that right? That is the ‘Cheng Zimin’ we are talking about, isn’t it?” Again, Lu the Lackey concurred.

“In that case I know him, but when did he become leader of the Axe Head Gang?”

“I understand he was elected by popular vote,” Lu replied.

“How does an old drug hound like him get involved with an assassination gang? If a strong gust of wind were to blow from the northwest it would knock him right over. If I were to push that scrawny addict with just my little finger, he would fly across the room and land ten feet away.”

“I have heard that that opium fiend doesn’t actually go out and fight himself, but dispatches others to do his dirty work for him,” was Lu the Lackey’s reply.”