Strange Pictures

By Uketsu

Translated by Jim Rion

(2022, translated 2025)

Harpervia

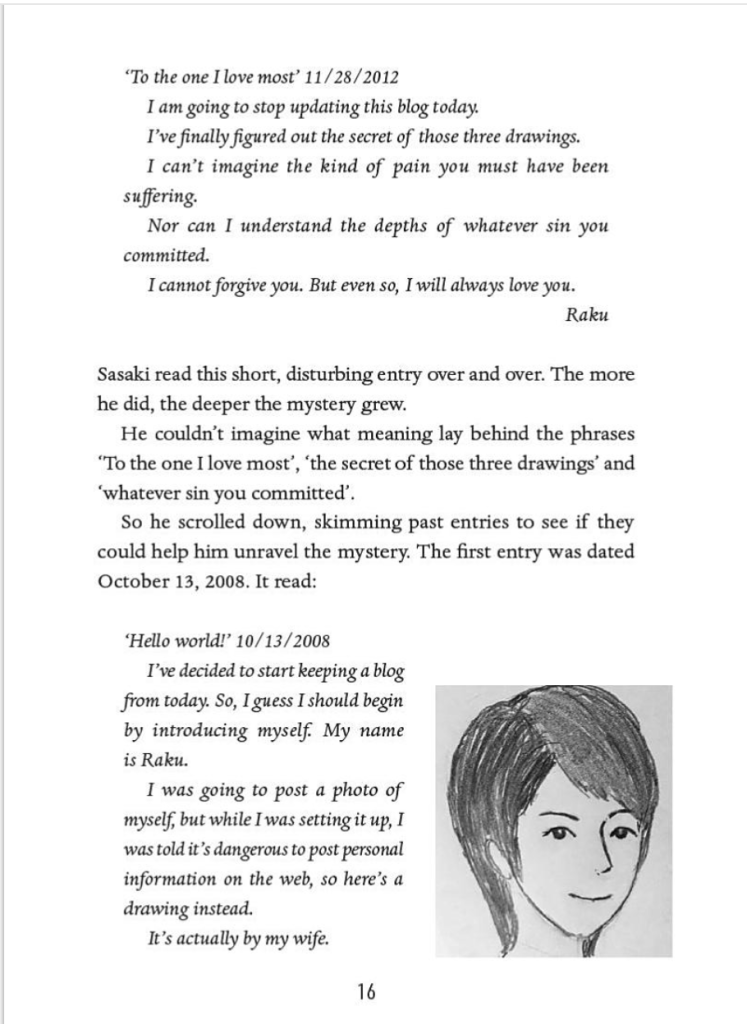

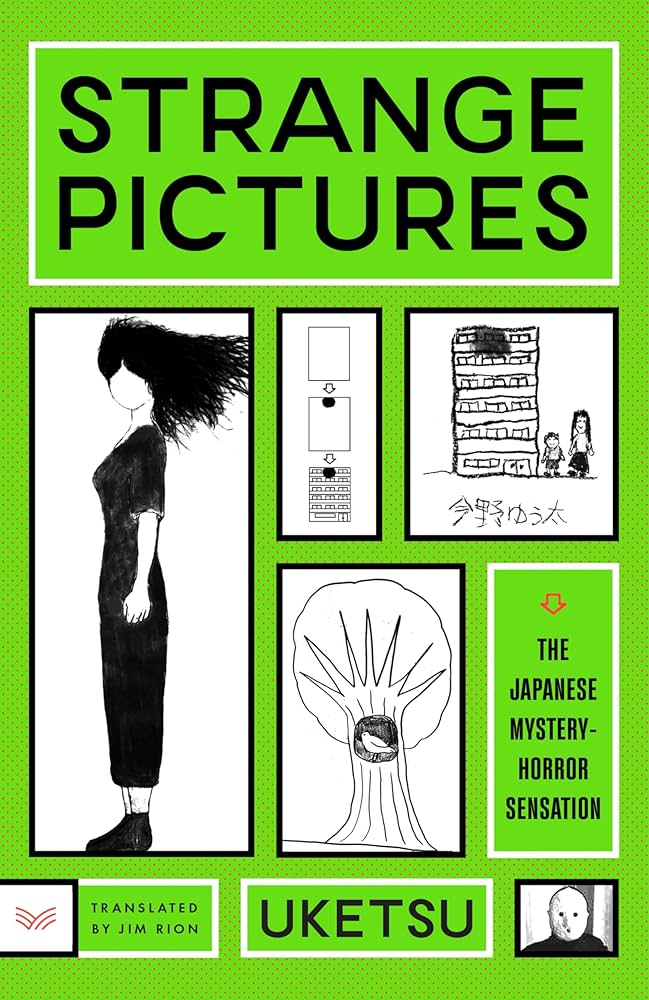

Uketsu is a contemporary Japanese writer who first came to fame posting surreal and grotesque video shorts on YouTube. Writing under the sobriquet “Rain Hole,” they always appear in a black body stocking and a primitive white mask, fielding interviews or reading from their work in a voice electronically altered to sound like a young girl. In 2020, they published a wildly popular 21-minute mystery on YouTube that required readers to imagine a crime based only on an analysis of a set of floor plans. Uketsu developed the concept into the publishing success, Strange Houses. Three of his novels have become bestsellers in Japan, including Strange Pictures. The novelty of the piece is appealing; each story features a drawing or a set of black and white drawings that are presented as puzzles for analysis. The first story features a psychiatrist at a hospital designed for children who have been convicted of criminal acts. As the child has managed their time in the hospital well and demonstrated their ability to work productively with professionals and fellow detainees, the doctor’s task is to review their criminal and medical files and determine whether they should be released. After careful study, the doctor feels assured that the child is repentant and able to continue their life as a free person. As a final proof of their assessment, they present the reader with a drawing the child created in one of their final interviews and demonstrate how various objects depicted in the drawing indicate that the child has overcome her past, completed her journey to wellness, and is ready to move forward with her life. Each story in the text involves a similar challenge: a hand-drawn image or images are collected as critical evidence, and professionals or amateurs must make inferences about the drawings that may help them solve or even prevent a crime. Some readers have balked at Uketsu’s drawings, claiming they are gimmicky and complain about “solutions” that seem unfairly abstruse. Perhaps they are, but Uketsu’s focus on the interpretation of drawings hearkens back to the early days of Japanese crime fiction, when writers like Edogawa Rampo and Keikichi Osaka became fascinated by the workings of new technologies like electric lights, cameras, and moving pictures were making the modern world both more accurate and “true” while also introducing new ways that human perception could be tampered with and reality might become less certain. Technology is prominent in the novel, as some of the pictures are found in an online diary, and the technology used by artists is essential to some of the revelations. The drawings all carry meaning, and each person who begins to study them is compelled to find the significance that eludes all others. Many assumptions are made and discounted, but some gain their own momentum, and when the analysis is shared with another viewer, the pair can sometimes play off each other and make rapid and inspired progress. That process of interpretation can be intoxicating, and Uketsu presents us with many examples where characters, despite their best efforts, misread the significance of or fail to grasp the full significance of a drawing. By turns comic and horrific, Strange Pictures is fast-paced and hard to put down–it is easy to see why the story is popular and why Uketsu has such a large fan base.