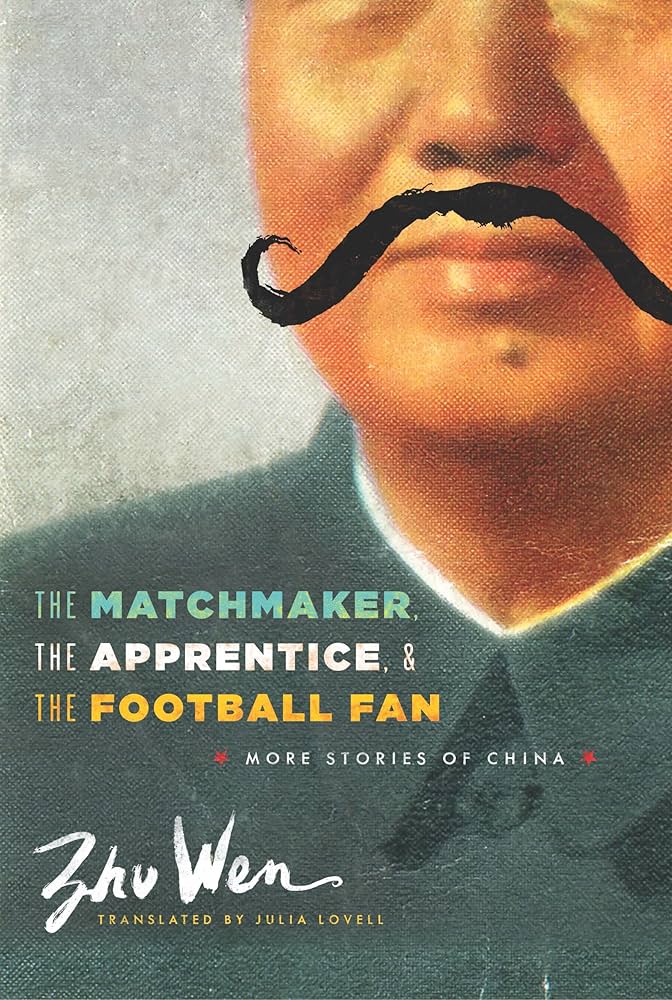

The Matchmaker, the Apprentice, and the Football Fan: More Stories of China

By Zhu Wen

Translated by Julia Lovell

(Translated 2013)

Columbia University Press

Zhu Wen’s collection of short stories, I Love Dollars, written in the 1990s and published in English in 2008, was ablaze with directionless, amoral characters who pursued money and sex in a world populated by cheats and rogues. In 2013, translator Julia Lovell returned to the 1990s to bring to light the short stories that comprise The Matchmaker, the Apprentice, and the Football Fan: More Stories by Zhu Wen. Apart from “The Wharf,” which was published in 2009, the stories are from the time Zhu was most active as a writer and before he moved on to filmmaking. Although his works continue to be published and sold freely in China, government critics have called him a hooligan and a writer of filth. The characters in this collection are less outrageous and unhinged than those in I Love Dollars; to some extent, they have grown up. The narrators in I Love Dollars are loose fireworks soaring and ricocheting in the dark, certain they will fly forever. In the more recent collection, characters are self-aware: they know their lives are empty and hope only to find others who have no further expectations from them. Zhu’s absurdist “Da Ma’s Way of Talking” features a colorless man who yearns for the good old days when he knew a selfish wildman named Da Ma. This larger-than-life figure was a scene stealer, a hot head, and a rule breaker. Loud just to be loud and absolutely reckless, he endangered and annoyed everyone. Years later, the narrator is certain that everyone he meets has a Da Ma way of talking, so he pesters people for information about the storied lunatic. Sure enough, many spent time with Da Ma, and each remembers him differently. Who is this Big Mama, this dangerous person whose voice was so influential that it altered the speaking patterns of everyone in China? And why, if he was such a terror, do so many think of him with such a powerful sense of nostalgia? “The Matchmaker” is another standout, featuring a man who is so sealed off against feeling that he still refers to school identification numbers when introducing us to his acquaintances. Like a remora clinging to a shark’s chin, he sponges off a former high school pal, suffering through bland, stingy meals, and sermons on the benefits of marriage, all for the sake of maintaining a useful party connection. He carries on an uninspired, mechanical affair with a married woman who may be as emotionally unavailable as he is: when they meet, they role-play as Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara or as Hamlet and Ophelia. While undressing and copulating, they mouth the lines of others to avoid revealing their true hopes and fears. Many of the stories focus on identity or its absence from the perspective of men living in dormitories and working on government engineering projects, or, as in “Reeducation,” people living in the shadow of their formative high school and college years. Zhu’s factory men come from everywhere and nowhere, relishing the opportunity to disappear into stereotypical roles and hide their identities by becoming their occupation; they almost sigh with relief when they are sent further away from their homes. Zhu’s humor is dark. The premise of “Reeducation” is that the party has determined that ten years on, those who were educated during the chaotic and shambolic Cultural Revolution have proven themselves to be the worst generation of Chinese, and therefore, now all sleepwalking through their thirties, they are called back for yet another round of reeducation, which the maladjusted citizens call “Operation Rebake.”

“Our seven-strong cohort—each of us had graduated from different engineering departments—had been put into a single dorm. We spent the first couple of weeks together at the training center learning about safety regulations. Since the factory was a long way out of the city, there was nowhere for us to go in the evening, so by the end of the first week we knew practically everything there was to know about one another. Here are the bald statistics that emerged: we had among us one Communist Party member, three former student officials, four winners of the State Education Commission Certificate for Undergraduates in English (level 4), one snorer, one teeth grinder, one neurotic, two sports fanatics, one holder of a National Basketball Refereeing Qualification (level 3), two planning to enroll for a PhD after working for a couple of years, one hoping to study abroad, and two with long-distance girlfriends. We were, on the whole, a cagey bunch, unwilling for the time being to declare personal alliances. But we were a special generation all the same, from a very particular context. We’d all taken to the streets during the spring of 1989; we’d all retreated from them in early June. This common ground gave us a greater sense of cohesion, a desire to know what each of us had gone through. And another week of sounding out one another had harvested a second, more intimate data set: two of us had been punished by the university authorities, three had had to retake exams, three had applied to join the party, one had hemorrhoids, two had been unhappy in love, four had smelly feet, one had more generalized body odor issues, one had a relative in the factory, one was a virgin, one had had TB, two suffered from unspecified stomach complaints, one had chronic hepatitis, one had ringworm on his thigh, and two had been circumcised.”

–from ”The Apprentice”