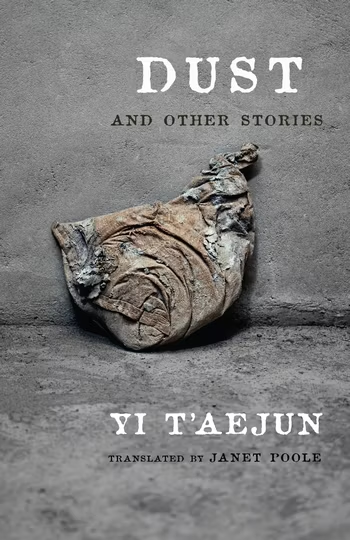

Dust and Other Stories

By Yi T’aejun

Translated by Janet Poole

Translated 2018

Weatherhead Books on Asia

Yi T’aejun (1904-early 1960s?) lived a complex literary and political life. At the age of five, his progressive father took him to the far eastern Russian metropolis of Vladivostok. His father passed away only a few months later, and Yi returned to live with his mother in Gangwon Province in what is now South Korea. When he turned eight, his mother died, and he stopped attending grade school, finding shelter and support at the homes of family relatives. He eventually enrolled at Hwimun High School, where he became known as a serious writer and earned a spot as editor at the school newspaper. Unfortunately, this position made him a target; he was wrongfully accused of inciting a school-wide boycott and expelled. With the help of a friend, Yi traveled to Japan and began writing essays and works of short fiction, which gained the recognition of Korean writers working in both Japan and Korea. One of his first works earned a prize from Joseon Mudan, and he began publishing his works in the newspaper JooGang Ilbo. Although he was accepted to the University of Sophia in Japan in 1926, he dropped out the following year, returned to Korea, and began work as a school teacher. In 1933, Yi founded the influential writers’ association, The Group of Nine, where he met Park Tae-won and Lee Ho-seok. During this time, he gained a reputation as an impassioned writer, editor, and educator. Then, in 1943, he returned to his hometown in Cheorwon County, which abutted North Korea. For the next several years, he worked with a variety of pro-North Korean political associations. Perhaps imagining he could return as easily as he left, in 1946, he quietly crossed over into North Korea. This decision was fatal. Joining up with other North Korean writers, he was able to travel to both Moscow and Leningrad. He continued to write in the North until 1954, when he came under investigation for his participation in The Group of Nine. His ideology was challenged by other North Korean writers, and he was purged. Although there is no record of his death, it is believed that he died in the early 1960s.

Janet Poole, the translator of Dust and Other Stories, provides an excellent overview of Yi’s career and his significance in 20th-century Korean literature. Poole points out that because of his defection, all of Yi T’aejun’s works were banned, and he was all but unknown in South Korea until 1988, when the Korean government finally withdrew its ban on publishing the work of writers who had “gone North.”. Today, his writing prior to his defection has enjoyed a positive rediscovery, and Yi is acclaimed as one of the many significant Korean writers of the 20th century, though many argue that his writing in the 1940s is marred by heavy-handed support for the North and outright propagandistic writing. Poole includes twelve of Yi’s short stories. All of them are steeped in a nostalgic worldview where narrators are keenly aware that the world they knew is changing in a total and irrevocable fashion. Yi is celebrated for rendering lively dialogue and capturing the colloquial speech of various regions and classes throughout the peninsula, shining a light on the experiences of women and rural women in particular, and zooming in on the conflicted world of Korean writers working under the Japanese occupation. Several of the stories feature Korean characters who let slip the degree to which they have abandoned their loyalty by their reliance on Japanese vocabulary and others refer to the moments the Japanese declared that Korean schools would begin teaching Korean only as an elective and finally banned the use of Hangul. Poole includes at least five stories Yi composed from 1938 to 1943, a period when he was clearly signaling his dissatisfaction with leadership in Seoul; his characters encounter an unappealing modernity and unravelling social contract. For the most part, they recognize what they regard as an unfolding tragedy but fail to act, choosing a principled passivity. Poole includes three works Yi composed after going North: “Before and After the Revolution,” “Tiger Grandma,” and “Dust,” works that merit attention on their own, yet are essential reading for anyone interested in North Korean Literature.

“But this ant-like repetitive life did not easily open its doors for these young women and girls. They were all busy and tied down by things that would not let them go. No small number of them had no one else to care for their babies, and the new brides among them were daughters-in-law, who had to fetch water from the well and returned home later than everyone else in the evening. After the evening meal, cotton ginning and spinning awaited them, or they would have to tie up straw into sheaves to store in the bags their husbands had woven. The members of the Children’s Alliance and the Federation of Democratic Youth knew that whatever kinds of strategies they employed, even if they encouraged the women a thousand or ten thousand times, their efforts would come to nothing if they did not first create the conditions where the barriers to those women attending the hangul school were removed. And so, the twelve members of the Children’s Alliance and six members of the Federation of Deomocratic Youth in Twenty Walls determined to relieve the women from their ant-like life.” – from “Tiger Grandma,” 1959