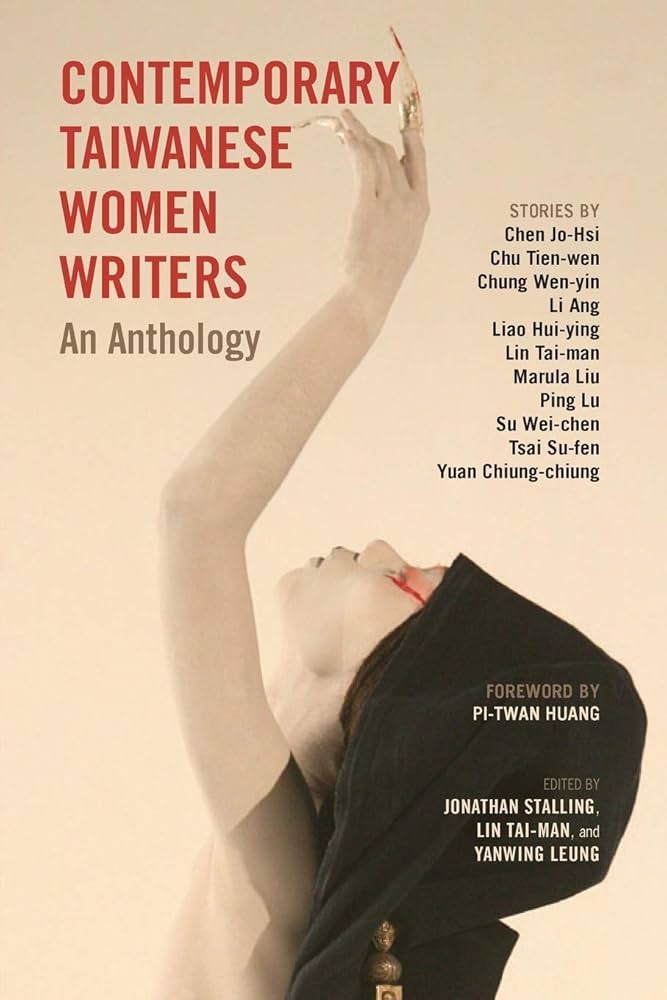

Contemporary Taiwanese Women Writers: An Anthology

Edited by Jonathan Stalling, Lin Tai-Man, and Yanwing Leung

2018

Cambria Press

The eleven short stories in this collection were written between the 1970s and the early 2000s; many were published in magazines and earned prizes. With the exception of Tsai Su-fen’s “Taipei Train Station,” which offers a critique of one uninspiring example of the city’s rush to modernity, and “The Fish,” Chen Jo-hsi’s tale of an old dockworker’s quest to bing home a fish for his ailing wife, this collection features female narrators navigating the turbid waters of love in a time of rapid social change while also renegotiating their relationships to their parents, siblings, in-laws, and children. Mothers loom large, as in Ping Lu’s “Wedding Date,” and Chu T’ien-wen’s “The Story of Hsiao Pi,” two nightmares of maternal dominance. In the former, a fatherless daughter becomes her ailing mother’s caretaker. An examination of filial duty gone wrong and love denied, the daughter all but becomes an old maid while her aging mother appears to recover the beauty of her youth. In the latter, a young woman recalls the extremes a neighbor’s mother went to change the path of her rebellious son. Lin Tai-man’s “Party Girl” and Chung Wenyin’s “The Travels and Lover of a Junior High Girl” feature the exploits of precocious young women who left their families in a bid to capture a rich husband or learn the art of writing at the foot of a Don Juan. In Maralu Liu’s “Baby, My Dear,” the urgent alarm of her biological clock goads a single woman in her thirties to find her path to pregnancy and a child who will love her unconditionally. Despite a lack of agency, several of the protagonists are on the cusp of taking control, as in Yuan Chiung-chiung’s “A Place of One’s Own,” when a put-upon wife turns the tables on her philandering husband, or in Liao Hui-ying’s “The Seed of the Rape Plant,” in which a woman confronts her father’s views about the insignificant fate of any woman, including his own daughter. Conditions unique to Taiwan flash here and there from the margins, but never more vividly than in Li Ang’s “The Devil in a Chastity Belt.” Set in a European city among a group of blacklisted Taiwanese patriots, we enter a between-world of political refugees, those who escaped the “Big Arrest” and can never go home. They are household names and icons, but they haven’t set foot in their country for more than a decade. If they return, will their enemies imprison or execute them? Will those who admired them still respect them? Will they recognize the island they left behind? Li’s piece might be the most experimental in this rich collection, but her daring pays off, offering new insight into political banishment, its impact on individual identity, and the arc of the hero.

“Liu Fen was two years younger than her and a divorcée as well. Hers was another kind of marriage. She had gotten pregnant in high school. Forced to get married, she never adjusted to married life and so had gotten a divorce. Before she turned twenty, all the important events in a woman’s life had already happened to her. Her mother raised the child. She took good care of herself, not looking at all as if she’d had a child already. She saw her husband often. She said, ‘As long as he’s not my husband, he’s really adorable.’” – from “A Place of One’s Own,” by Yuan Chiung-chiung