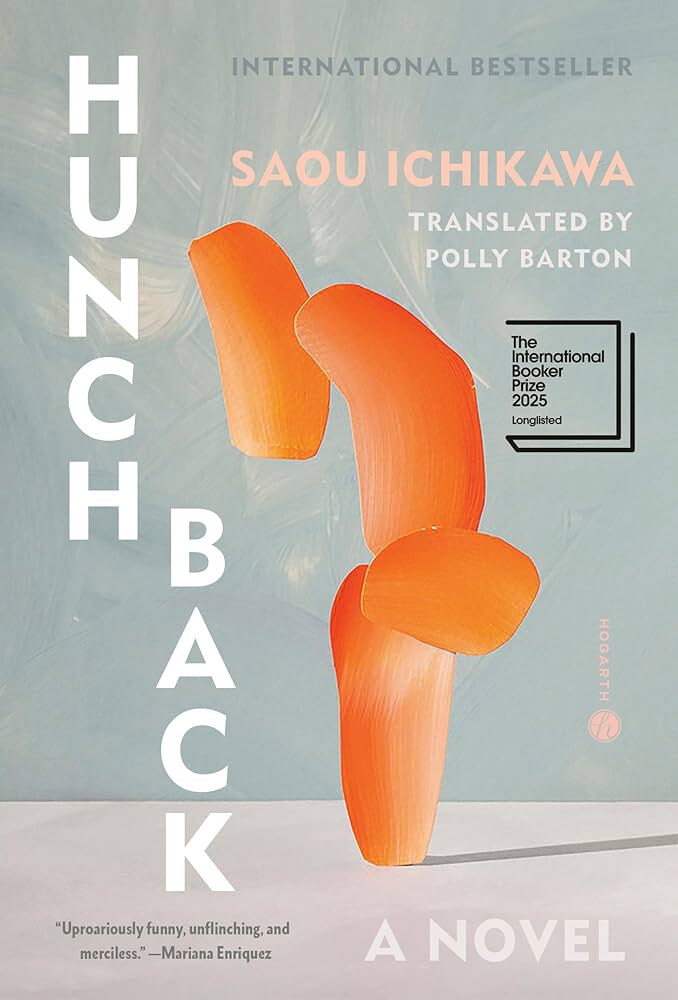

Hunchback

By Saou Ichikawa

Translated by Polly Barton

(2023, translated 2025)

Penguin Viking

In Hunchback, Saou Ichikawa’s witty, titillating, grotesque, and accusatory novella bristles with ideas about the body, the self, and society. From the start, Saou plays with avatars and avatars-of-avatars, as well as a multiplicity of voices and genres. Significantly, the author and her protagonist are women who endure a similar medical condition. Saou and her creation, Shaka, both suffer from myotubular myopathy, a genetic disease that causes a profound weakening of the muscular system. Readers may be tempted to search for Saou in Shaka and Shaka in Saou, but Hunchback is neither a memoir nor a traditional Japanese I-novel. Like Saou, Shaka is a writer, but she makes her living by writing pornography for an online sex site. Thus, when we first encounter Saou’s protagonist, they appear to be a hyperoused, able-bodied man in flagrante delicto with comically large breasts. Yet he is only one of many caricaturish beings in Shako’s stable of lusty, privileged, and orgasm-oriented creatures, fictional beings on whose labors she makes a steady income; her email exchanges with her editor also serve as one of her few social outlets. Saou’s protagonist also identifies as Shaka, referencing Shakyamuna Buddha, and speaks of the luxury home cum hospital room she inhabits as the Nirvana in which she wanders in her specialized motorized chair. As seen above, Saou’s protagonist interacts with the world primarily via the web, which is also where she takes classes on disability rights, the representation of disability in history and literature, and medicine. This device allows her to shift quickly into sophisticated and sharp-toothed critiques of our culture of physical perfection, our tendency to pity and other people with disabilities while still somehow managing to deny them their humanity, and aggressive and even violent movements to strike back against acts or inaction of the able-bodied. Shaka also inveighs against society’s tendency to view those with physical disabilities as inherently asexual or incapable of feeling or engaging in sexual relations or even feeling desire. Saou’s Shaka strikes out at many targets, and her attacks cut deep. Few will come away unscathed. Yet she also reveals a deep loathing of her body or her self that is terrifying in its irrationality and challenges her claim to be the awakened Shakyamuni. I imagine reading and rereading this text over the next few years, and I hope to share the experience with a Buddhist, especially to discuss the tradition that Gautama Buddha was himself a hunchback.

“Japan, on the other hand, works on the understanding that disabled people don’t exist within society, so there are no such proactive considerations made. Able-bodied Japanese people have likely never even imagined a hunchbacked monster struggling to read a physical book. Here was I, feeling my spine being crushed a little more with every book that I read, while all those e-book-hating, able-bodied people who went on and on about how they loved the smell of physical books, or the feel of the turning pages beneath their fingers, persisted in their state of happy oblivion.”