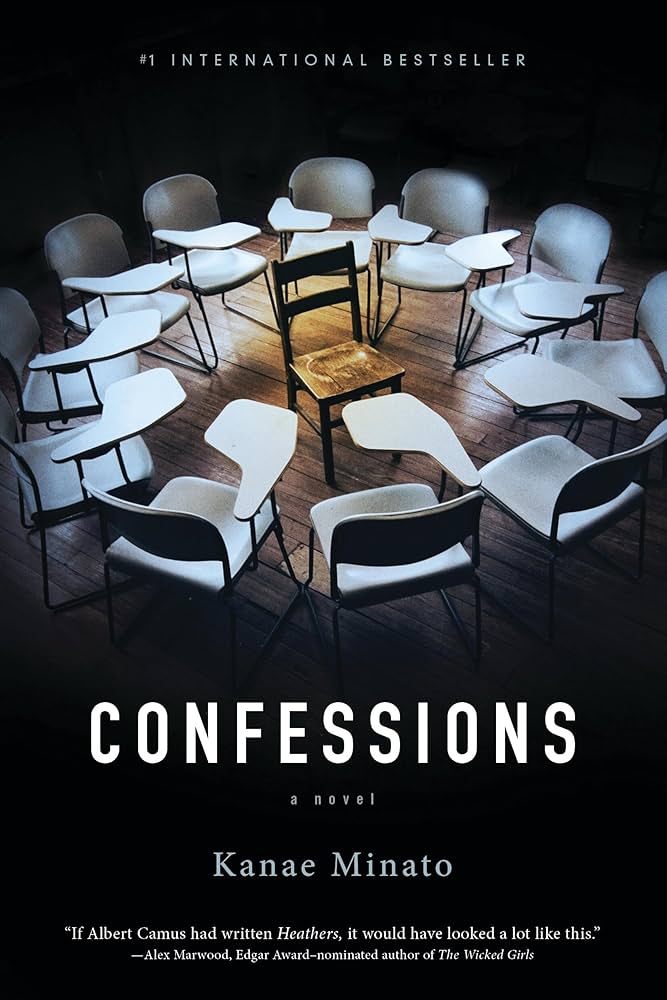

Confessions

By Kanae Minato

Translated by Stephen Snyder

2008, translated 2014

Mulholland Books

Readers familiar with Koushun Takami’s 1996 dystopian novel, Battle Royale, and Mieko Kawakami’s Heaven (2016) know that bullying, violence, and madness are often center stage in novels about Japanese Middle School. A milder form of existential terror arises in the recent international bestseller, Lonely Castle in the Mirror (2022), by Mizuki Tsujimura. Kanae Minato’s debut novel, Confessions, enters the fray with a psychological thriller about a middle-aged single mother who retires early from her position as a middle school teacher following the accidental drowning of her four-year-old daughter in the school’s swimming pool. Kanae, who works as a Home Economics teacher, tells the story of the teacher and her pupils from multiple points of view. Each section of the novel features a lengthy, extended monologue from a different speaker. The first is delivered by the retiring teacher to her class. In it, she reveals her upbringing and her decision to become a teacher, as well as the unforeseen and hurtful costs she has had to pay for engaging with emotionally disregulated, immature, and impulsive students. She also explains her relationship with her daughter and the extent to which she still suffers from having lost her. And she shares too much when she discusses the intensity and complexity of her relationship with the man who was her daughter’s father. Nothing, however, could prepare her students for the climax of her farewell address: she declares that two of the students in the classroom murdered her daughter, and that since she believes that their status as minors will allow them to escape justice, she has prepared and executed her own judgment. Much of the story depends upon a logic-defying lack of communication and transparency between spouses sharing the same home and school administrators and teachers, and the lengthy uninterrupted monologues can seem drawn out, repetitive, and too on the nose. And yet, Confessions makes for compelling reading. Why does evil exist, and how can it manifest and flourish in children? Kanae’s characters acknowledge that Japan is not a particularly religious country, but shouldn’t parenting and school culture create young citizens with a strong sense of right and wrong and an abiding regard for human life? Parents are clearly at fault for failing to recognize disturbing behavior in their children and others engage outright physical abuse, but the perpetrators themselves wonder aloud if their actions can be fully explained by the degree to which their parents sinned against them through commission or omission. In the end, the most interesting questions should be addressed to the teacher who applies her own justice and punishment to the morally bankrupt children in her care.

“But even then, it takes a certain amount of courage to be the first one to come out and blame someone else. What if no one else joins you? No one else stands up to condemn the wrongdoer? On the other hand, it’s easy to join in condemning someone once someone else has gotten the ball rolling. You don’t even have to put yourself out there; all you have to do is say, “Me, too!” It doesn’t end there: You also get the benefit of feeling that you’re doing good by picking on someone evil—it can even be a kind of stress release. Once you’ve done it, though, you may find that you want that feeling again—that you need someone else to accuse just to get the rush back. You may have started with real bad guys, but the second time around you may have to look further down the food chain, be more and more creative in your charges and accusations.”