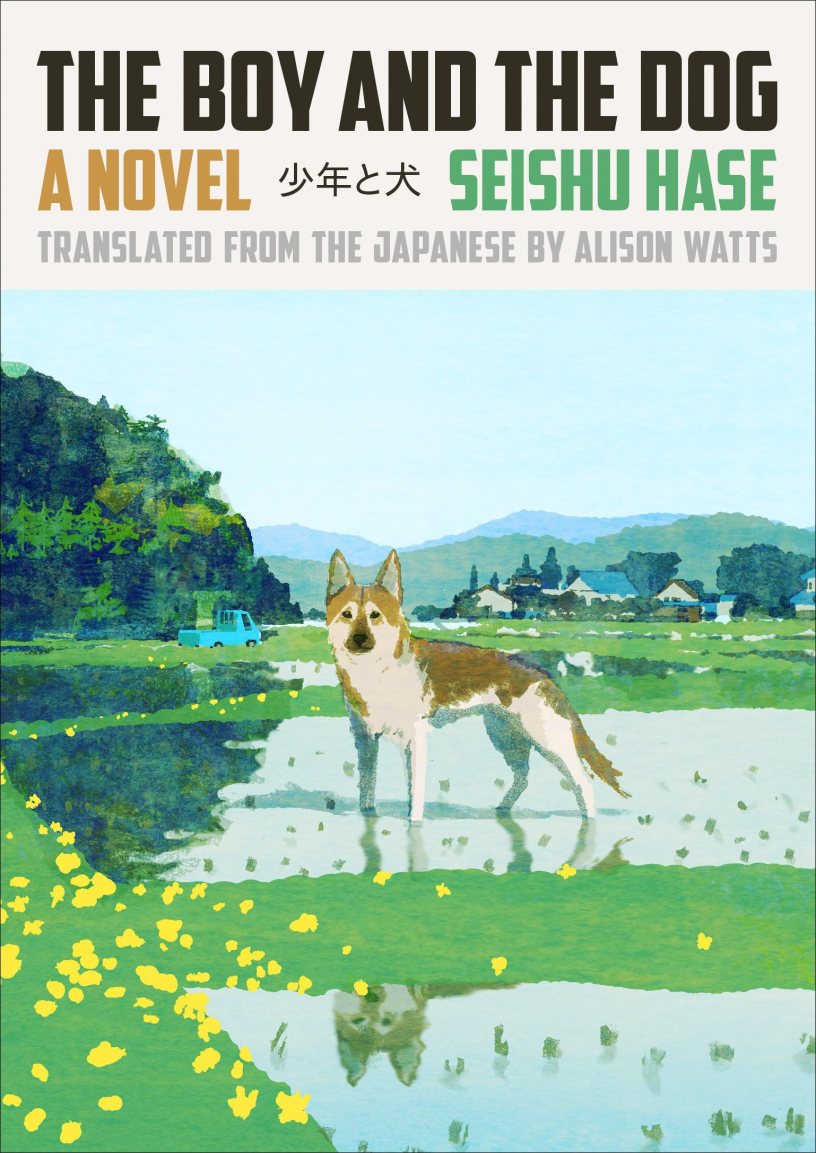

The Dog and the Boy

By Hase Seishu

Translated by Alison Watts

(2020, translated 2022)

Viking

At its heart, The Dog and the Boy is a novel rooted in “the triple disaster,” the earthquake, tsunami, and the ensuing Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident on 11 March 2011. The story begins six months later, when a down on his luck young man discovers an alert and obviously hungry dog waiting at his vehicle. A German Shepherd, Japanese native mix, the dog wears a scuffed collar bearing the nameplate “Tamon.” Immediately attracted by the obvious intelligence of the dog and by the clear signs of careful training, the man adopts the dog into his life. He introduces the dog to his sister, who wonders aloud whether he is responsible enough to care for it. She reminds him that he has been unemployed and adrift since the earthquake and his debts are rising. He feels guilty that he has failed to offer any economic support to the family, and ashamed that his sister has taken on the filial burden of caring for their mother, who is suffering from dementia. Rather than seek employment in the post-disaster reconstruction efforts, he seeks easy money through his connection with a low-level thief he met in high school. He also begins visiting his mother more frequently. Usually affectless, she brightens when she meets Tamon. She believes the dog is her childhood pet, and the instant connection they develop brings the old woman to life, inspiring her to go for walks and become more talkative. The brother and sister agree that the dog is extraordinary and conclude that Tamon must come from Tamonten, one of the Seven Lucky Gods, a protector of sacred sites; they and other characters regard the dog as a guardian angel. Though the young man loves the dog, he recognizes his relationship with Tamon must be temporary, as the collar and the dog’s training indicate that he was no stray and he should be returned to his master. He also believes that however content the dog appears to be, it is clearly searching for something or someone to the south. And so begins a pattern: the dog enters into a relationship with a human or humans, they provide it with food, shelter, and love, and then the dog is allowed to–or must–move on. Tamon’s journey last six years, during which he spends time with a variety of different lonely and needy humans as well as long periods wandering in the wild of Japan’s mountains, trying to find its owner. Hase constructs the dog’s journey as it impacts each person who takes the animal into their heart. Hase makes it clear that their is some ambiguity whether Tamon’s temporary caregivers chose the dog or the dog chooses them. Many of the characters note the dog’s “will” as well as its diligence and persistence. A character’s time with Tamon can be short or quite long, but the points of contact deliver memorable scenes. The Dog and the Boy was a runaway success in Japan as a “healing novel,” a feel good, uplifting tale of love and recovery in the wake of the triple disaster.

“She put down her pen and laid a hand on Clint’s back. Dogs were sensitive to changes in human moods. She didn’t want him getting anxious because of her own irritation.

“I’m a bit on edge. Did I bother you?”

Clint lay down at Sae’s feet with his face pointing outside. Sae had noticed that Clint always faced west. Southwest, to be precise. What was in the west? Sae asked Clint the question many times but of course got no answer. Was it simply coincidence? Or maybe his home was in the west?

Sae had posted a photo of Clint on social media to try to find his owner. A dog as well-trained as he was undoubtedly had been loved by somebody. If he had become separated from his owner due to some mishap, that person would be frantically searching for him.

But she got no response. Not even a scrap of information that might offer some clue.”