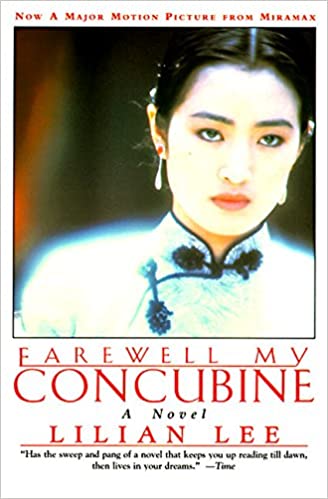

Farewell My Concubine, By Li Pi-hua (Lillian Lee)

Translated by Andrea Lingenfelter

(1985, revised 1992, translated 1993)

Harper Perennial

(Novel)

Li Pi-hua aka Lillian Lee wrote The Hegemon King Bids Farewell to his Concubine in 1985. She co-wrote the screenplay for the movie Farewell My Concubine with Wei Lu. After the success of the movie, Li revised her novel to more closely reflect the dramatic changes that were made to the original ending. The story begins in the opening days of the founding of the Republic of China. A desperate mother brings her young son to the manager of a ragged “school” that prepares young orphan boys for performing traditional Peking Opera. The boy she abandons, Cheng Dieyi, is delicate and beautiful. The other orphans torment Cheng, but early on, Duan Xialou, a respected older boy, declares that he will be Cheng’s protector. As the years pass, the talents of the two young men earn them leading roles. In the tradition of the all-male opera, Cheng develops his feminine traits, his ability to move and sing like a woman, and his skills in stage makeup and costume. Meanwhile, Duan grows stronger. He becomes an expert in martial arts, and his natural charisma and leadership skills make him the perfect embodiment of a whole range of Chinese generals. The two are paired as lovers in hundreds of performances, but Cheng is the real star. He attracts the attention of powerful men who sexually exploit him and set him up as a kept woman, but Cheng is only ever in love with his great general, Duan. Duan is always aware of Cheng’s desire; he certainly manipulates the young man’s emotions to his advantage. But Duan falls in love with a beautiful prostitute, Gong. When she buys her freedom from her madam, she compels Duan to marry her, beginning a brutal war of wills between her and Cheng, who will spend years fighting brutal battles for their great general’s attention. The fury of the romantic triangle is only equaled by the political turmoil the opera witnesses, from 1924 to the 1970s. The fate of the opera ebbs and flows dramatically during these years. Cheng makes too many compromises with the Japanese during the occupation, and the two friends are forced to humiliate each other during the public trials of the Cultural Revolution, yet they live long enough to see their nation attempt to recuperate the art form for reasons that are commercial and perhaps political. Cheng is an extraordinary creation: his fateful birth (he was born with an extra finger), captivating beauty, sexual ambiguity, and consuming love for only two things, art and his partner, make him a fascinating witness and interpreter of fifty years of political and social upheaval.

A performance is a brief encounter between actors and audience. Its sweetness lies in its brevity and its melancholy aftermath. A performance lets the actor be someone important, while those in the audience have bought a piece of that extraordinary life. The actors bask in the admiration of hundreds of strangers who are transported out of their small lives by the deep emotions enacted before them. But the encounter only lasts for several hours of an evening. By the next day, all of the participants have returned to their quotidian existence, strangers again. (83)