Seopyonje: The Southerner’s Songs

By Yi Chung-jun

Translated by Ok Young Kim Chang

(1993, Translated 2011)

Peter Owen Publishers

(Connected Short Stories)

Seopyonje: The Southerner’s Songs is a collection of five short stories: “Seopyonje,” “The Light of Songs,” “Immortal Crane Village,” “Bird and Tree,” and “The Rebirth of Words.” Each can stand alone as a marvel, but as the stories are connected by common themes and characters, readers will discover that the overall effect of Yi’s project is far greater than the sum of its parts.

At the core of the stories is a tale of personal and cultural loss. A family of the entertaining class–a group already marginalized–is struggling to make a living performing traditional Korean music at a time when radios have made their way into every rural hamlet and tastes are turning to Western pop. They perform pansori, an extraordinary presentation of one of ten surviving folktales from the genre–the few that have not been lost to time. To sing a tale might require the vocalist to sing six to eight hours at a time. The content of the stories is elaborate, but the genre depends on harrowing minimalism. Pansori artists perform something like an opera, but there are only two people in a cast: a singer and an accompanist who plays a simple hand drum. If the genre were not already challenging enough, female performers are required to sing in a voice described as “husky” or man-like.

The core story revolves around characters whose identities and actions would be familiar to those who appreciate the work of the Greek tragedians. One fateful night, while sheltering in a storm, the wife of the pansori teacher goes into labor. The mother is in agony. Her son watches in horror as his stepfather attempts to help her deliver the child. That night, the son witnesses the birth of his stepsister and the death of his mother. Afterward, the family of three continues its wandering,, the father always singing. He teaches the boy to play the drum accompaniment and the daughter to sing. The daughter’s talent is exceptional, but tastes are changing and the audience for the traditional performers is waning. Meanwhile, the son is fighting a secret obsession: he has become convinced that his stepfather murdered his mother and yearns to avenge her death. Each night the boy feels the overwhelming desire to murder his stepfather rise in him with the power of a blazing sun; however, the father’s passionate singing and his embodiment of all human suffering work a powerful influence over the boy’s soul, inexorably returning to him his senses of moderation, humanity, and forgiveness Caught in an endless cycle of simmering rage and calm resignation, the young man decides he must flee the family rather than destroy it. To reveal any more of the plot is to tell too much and to diminish the agony that is at the core of the story cycle.

The remaining tales in the collection expand to embrace ruminations on ecology, man’s place in nature, loneliness, interconnectivity, and the ineffectiveness of words and language to convey human suffering and truth. Yi’s characters debate form and content, the failure of modern systems of education, commercialism, capitalism, and the tension between the ideals of the dwellers of cities and villages: how must one live? As his project unfolds, Yi’s narrative strategies become ever more nimble and daring as he confronts essentially Korean ways of knowing. For example, he wrestles with the concept of han, “a fateful, insoluble anguish – unremitting regret and unrequited grudges – that had been embedded in the soul of [the] people,” recognizing the power of suffering and the resilience of the Korean people while also questioning its psycho-emotional weight. Likewise, Yi makes the concept nunchi, the social skill of intuiting other people’s minds or assessing a situation, so real as to be almost palpable, as he allows us to hear characters anticipating what their interlocutors might say next or where they may be leading them. In the final stories, all speakers are performers, playwrights, scenic artists, and directors, desperately trying to communicate ideas so vital that words alone will only fail. In some cases, characters have waited a lifetime to pass on an insight they themselves have struggled to put into words, realizing at last that the only way they will be able to comprehend that insight fully is to share it with another through not spoken words and carefully crafted gesture of release or restraint.

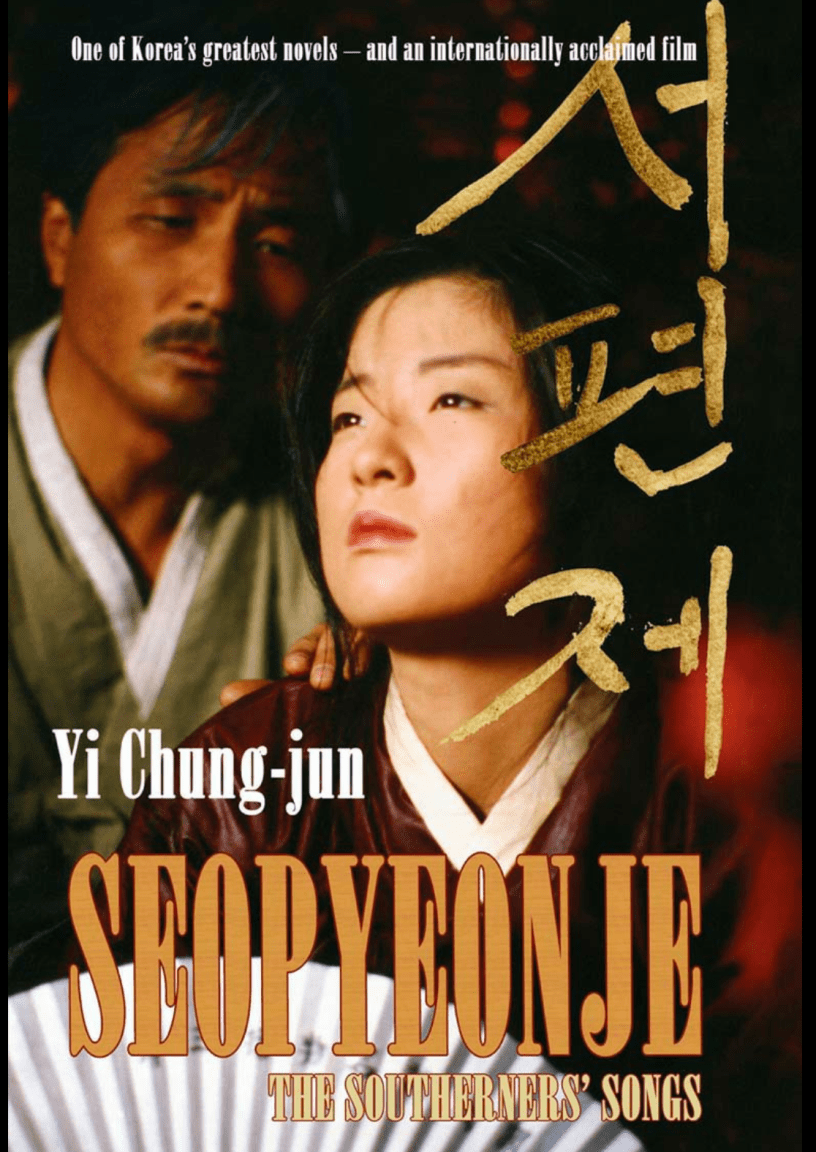

In 1993, director Im Kwo- taek brought the title story to the screen. The film broke all attendance records in Seoul and sparked renewed interest in the folk art of pansori. Prior to the film’s success, South Korean filmmakers tended to imitate western-style productions and themes. Seopyonje ushered in a new interest in filmmakers who were striving to create a uniquely South Korean point of view. Seopyonje was shown at Cannes, earned six Korean Grand Bell Awards, and won an honorary Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival, all of which helped the film garner worldwide recognition.

“The traveler remembered the host’s remark when he had asked what had happened to the trees he had planted on the poetry man’s land. The man’s reply was: ‘I left them alone there. I see no reason to dig them up and move them somewhere else. Even a blade of grass has its own life, and that life doesn’t belong to me. People tend to manipulate living things, moving them around at will, because they think they own them. If you tamper with others’ lives, yours will also be tampered with. Human beings as well as trees must stay where they belong, each in its own place. A tree has rights just as it has life.’”

Reading Seopyonje: The Southerner’s Songs was an emotional rollercoaster for me. Yi Chung-jun’s writing is raw and powerful, exploring themes of personal and cultural loss, human suffering, and the resilience of the human spirit. The tale of the pansori artist and his family touched me deeply, as I watched them struggle to make a living in a world that no longer values their traditional music. Yi’s exploration of han and nunchi added a unique cultural element to the story, making it feel all the more real and authentic. This collection of short stories is a must-read for anyone who appreciates deeply moving and thought-provoking literature.

LikeLiked by 1 person