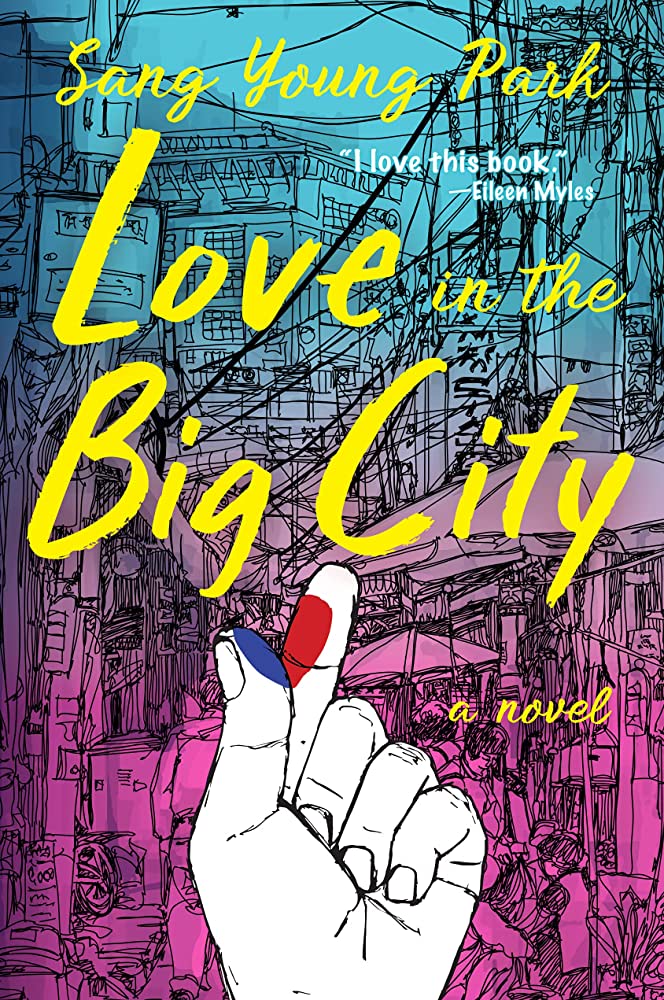

Love in the Big City

By Park Sang Young

Translated by Anton Hur

(2019, translated 2021)

Grove Press

(Novel)

Park Sang Young’s Love in the Big City is a collection of novella-length stories about young gay men in Seoul, a city that acknowledges the existence of homosexuals while also denying them civil rights. When his book was first released, many readers and critics assumed that Park’s work was largely autobiographical; that is not the case. The stories are all about relationships, and many, if not all, are profoundly unhealthy. “Jaehee” is about a beautiful young woman who appears to have thrown herself entirely into a hedonistic lifestyle of clubbing, drug abuse, and casual sex. She and the gay male narrator, who shares Jaehee’s lifestyle, are adrenaline junkies, depressives, enablers, and codependent. The narrator, who throws himself into the arms of any man in the hopes of finding true love and a long-term relationship, is envious of Jaehee’s ability to attract men, enjoy casual hookups, and walk away from longer trysts without shedding a tear. When they part ways, the narrator is almost certain that Jaehee is on the path to self-destruction. So he is stunned to hear from her many years later, having somehow found herself recalled to life and reinvented as the wife of a successful businessman. Meanwhile, the narrator’s life has not changed in any significant way and he is very much the lonely, love-lorn man he was in his twenties. “A Bite of Rockfish, Taste the Universe,” begins with a letter from a former lover who has written both to congratulate the thirty-something narrator on publishing his first novel and return his diary, which the narrator hurled at him five years ago just before walking out of his life. The letter and its contents upend the speaker’s life. He is not currently in a relationship, but he fears an encounter with his old lover. Stricken by fear, his first impulse is to run to his aging mother, who is in an assisted living center and suffering from cancer of the uterus. It may appear the narrator spends hours with his mother out of love and filial piety, but there is no mutual aid in this relationship: his mother is nothing less than a terror who may boast about his success in public but accuses him in private of exploiting her suffering in order to write novels and derides him for his pursuit of men. Reeling from that firehose of resentment and hostility, the narrator reflects on the writer of the letter. Haunted by the abusive mother, he reminisces about their first meeting at University in a class with the remarkable name, “The “Philosophy of Emotions.” He speaks longingly of the tall man’s dark clothes, elaborate tattoos, aloof look, and honed body. Like many of Park’s wounded, self-loathing narrators, this man is stunned to discover that such a person would desire him, and so they begin a wildly unequal and powerfully self-destructive relationship. Not surprisingly, the dark-hooded figure from his past was delayed in contacting his ex because they never used their real names. As Park develops their story, it is clear that the narrator’s best hope of coming away in one piece from this encounter with his past depends entirely on the small comfort his precociously cruel mother can offer. “Love in the Big City” is unique in that the narrator is young, hopeful, and more self-aware and self-assured. Just back from his first leave in military service, he tests positive for HIV. Far from taking this news as a death notice, the narrator accepts the reality of the disease, owning and renaming it. It becomes a part of his life. He talks candidly about his treatment and the effects it has on his body and mind. An honest and trusting person to begin with, the disease has the effect of supercharging his candor. He continues to seek relationships and have sex, but he does so in a deliberate, intentional manner. He finds that he communicates more openly with straight and gay people about his disease. Unlike the characters in the earlier stories, shame slips from him like a robe following a bath. He hangs it behind the door and moves on. One would struggle to imagine reading such a tale in the 1980s, but in the 2000s the character has the gift of a new cocktail of drugs that will keep his disease in check, allowing him to envision a life in which love is possible. The final story in the collection, “Late Rainy Season Vacation,” focuses on a man who tries to salve the wound of his break up with Gyu-Ho–a serious spiral into a depression so significant that he winds up quitting his job and contemplates spending the remains of his savings in a fling in Thailand–by doom-scrolling his way through Tinder. There he discovers a man who has gone to great lengths to conceal almost every element of his identity. They agree to meet in a posh hotel in Bangkok, where he learns that his date is both significantly wealthier and more closeted than he had first imagined. He is also married. The narrator spends his nights in the hotel room in the arms of a man whose name means “love,” but during his days he still wrestles with his memories of staying at the same hotel with Gyu-Ho, a compulsion that bodes ill for the narrator’s chances of recovering.

“Hello. It’s hyung. I heard you’ve become a writer. Congratulations. I thought your real name had a “je” in it, am I right? You must be using a pseudonym.”

This idiot. He couldn’t even remember the name of someone he’d gone out with for over a year.

“You’ve gained so much weight that I didn’t recognize you at first.”

Fuck it. I’ve read enough. Tear this shit up. But then, the next sentence:

“I wonder if your mother’s doing better now. I’m sorry about before. About a lot of things. All of it.”

Why do men always apologize to me? Just don’t do the thing that will make you apologize in the first place. Then, just as he always did, he went on talking about himself.

–from “A Bite of Rockfish, Taste the Universe”